Some times it is hard not to wax philosophically–perhaps even sentimentally when, as a bit player in academia, I find myself immersed in institutional forms of collegial exchange that are also rituals of renewal. At such moments I cannot help but feel my place in a certain genealogy. These situations are not without their ironies but they often force us to confront the rapid passage of time. (Wasn’t it just yesterday that I was a young whippersnapper?) Anyway, here are three such recent moments for me.

Exhibit A: October 19th. I will start on a personal note. My daughter Hannah Zeavin, who is a second year Ph.D. student in the Department of Media, Culture and Communication at NYU, organized a panel which she submitted for consideration at the annual SCMS (Society for Cinema and Media Studies) conference to take place this coming March in Seattle. As it turns out, I submitted a workshop proposal to the same conference. Yesterday we found out that hers was accepted while mine was turned down. Since I am connected with another panel that was also accepted, we are going to attend our first joint conference. But about those ironies…

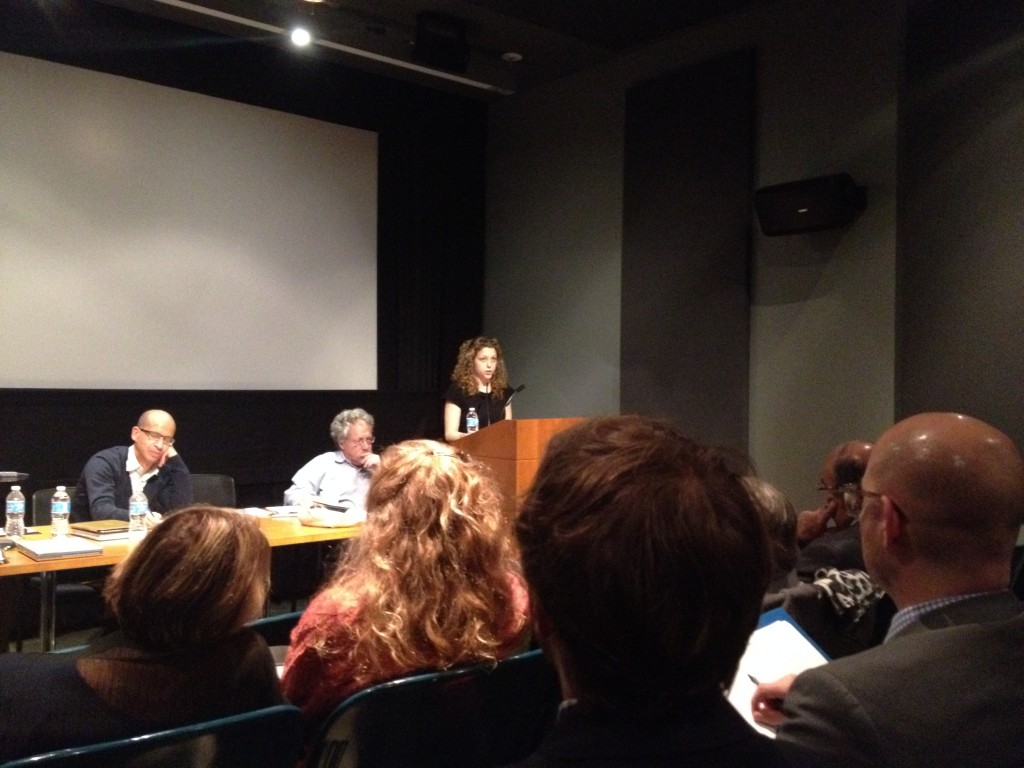

Jonathan Kahana, Dana Polan and Hannah Zeavin.

Photo by Dan Streible

Is not a picture worth a thousand words? Perhaps it helps if one knows the back story. Jonathan Kahana flew to New York from the West Coast to be on this panel at NYU’s Department of Cinema Studies with Hannah and Dana Polan. They were examining John Huston’s documentary Let There Be Light (1946), which I have certainly taught more than once at NYU many years ago when I was an adjunct there. Before the event, Jonathan gave me a call to express his sense of disorientation. He and I had been on a panel together at the previous SCMS conference. Now he was on a panel with my daughter. Dana’s presence is also worthy of comment, for he played a small but interesting role in Hannah’s early intellectual development. As a very young girl (would she have qualified as a toddler?), Hannah had figured out that people whose first name ended with an “a” sound were female. Her own name being a good example but there were many others (Noa Steimatsky or Gloria Monti, for instance). So she was beginning to figure out the apparent logic of how this world operates––and then Dana Polan dropped by. She was visibly puzzled since he violated her understanding of how the gendered world was organized and named. It was probably her first act of necessary intellectual revision.

I was not at this occasion but the event was documented by Dan Streible, who had crashed on my couch many years ago when he was doing research in NYC. Hannah was about five and he brought a reading glass as a kind of house present. Hannah was immediately fascinated about this instrument of investigation and she would ask about Dan (the man with the magnifying glass) for many years afterwards.

Dan’s joint portrait

Now let me add one more fact–– about that workshop that I proposed, which was turned down. Jonathan Kahana was supposed to be one of its members. In fact, its chair.

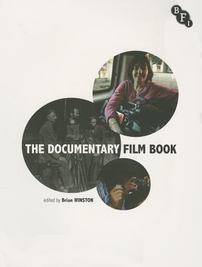

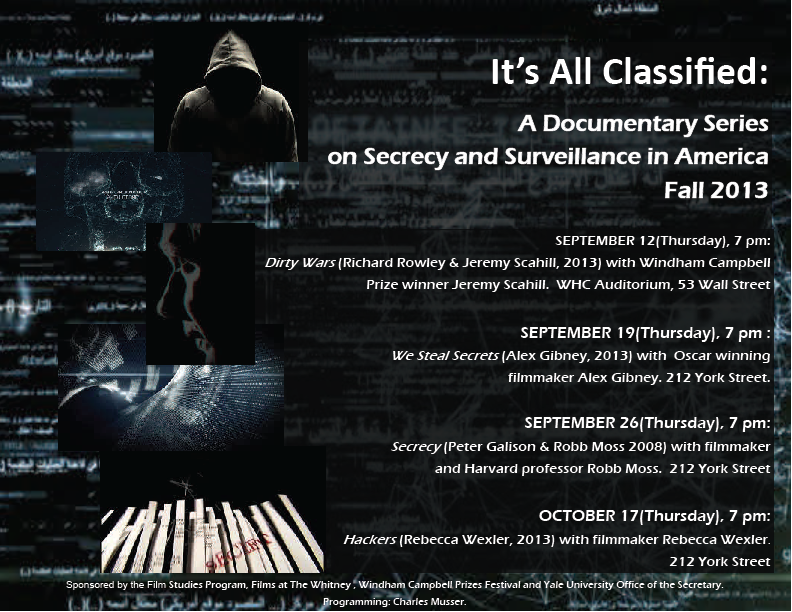

Brian Winston Comes To Yale

Exhibit B: November 4th. I took my first course in the history of documentary with Brian Winston at NYU’s Cinema Studies department––it must have been in the late 1970s. Almost a decade later, after the success of my documentary Before the Nickelodeon, I had the chance to teach the same course––filling in for George Stoney who was pursuing other opportunities. It proved to be one of the more disconcerting experiences of my life as I periodically heard myself  channeling Brian during my first year of lectures. I was speaking Winstonese. By then Brian had left NYU for Penn State, then University of Wales (Cardiff) and is now at University of Lincoln (England) where he was Dean of Communications and briefly a Pro Vice Chancellor. Currently the first Lincoln Chair of Communications at that University, he was touring with his newly published anthology, The Documentary Film Book (BFI/Palgrave, 2013)––to which I made a contribution: “Problems in Historiography: The Documentary Tradition Before Nanook of the North.” It presents a much longer historical trajectory of “the documentary tradition” even as it strives to think through issues involving genre and media specificity that the field of documentary studies needs to address. Here I will note that there is a certain tradition of student’s work appearing in collections assembled by their teachers and mentors. Some 35 years later, Brian and I finally pulled it off. What’s interesting is that Brian looks pretty much the same as he did in 1980. Wish I could say the same.

channeling Brian during my first year of lectures. I was speaking Winstonese. By then Brian had left NYU for Penn State, then University of Wales (Cardiff) and is now at University of Lincoln (England) where he was Dean of Communications and briefly a Pro Vice Chancellor. Currently the first Lincoln Chair of Communications at that University, he was touring with his newly published anthology, The Documentary Film Book (BFI/Palgrave, 2013)––to which I made a contribution: “Problems in Historiography: The Documentary Tradition Before Nanook of the North.” It presents a much longer historical trajectory of “the documentary tradition” even as it strives to think through issues involving genre and media specificity that the field of documentary studies needs to address. Here I will note that there is a certain tradition of student’s work appearing in collections assembled by their teachers and mentors. Some 35 years later, Brian and I finally pulled it off. What’s interesting is that Brian looks pretty much the same as he did in 1980. Wish I could say the same.

Here is the important point: Although Brian Winston came to Yale to discuss “The State of Documentary Studies Today,” it was not me who brought him to Yale. Film Studies Program chair John MacKay and Brian are part of a European-based group which is studying the newsreel. John was eager for Brian to stop off at Yale while on his US tour, and I volunteered to organize it. John, as I remind him all too frequently got into Film Studies in significant part by being a teaching assistant in my two lecture courses (Intro to Film Studies, Film Theory and Aesthetics), for its in there that he saw his first two Vertov films. And so I happily find myself the indirect relay.

Much of Brian’s talk reprised his introduction to The Documentary Film Book, which I saw in print for the first time when he arrived with book in hand. I am always intrigued with the different histories of documentary, which vary depending on nation (or even locale) from which they originate. To some degree there is an Anglo-American variant but Brian made me realize that as a Brit, he has had to struggle with the hegemonic influence of John Grierson far more than have many American practitioners. (I was exposed to Vertov and Cinema Verité long before I read anything by Grierson.) The discussion got more interesting––and certainly more passionate–– when Brian turned to contemporary documentaries.

Much of Brian’s talk reprised his introduction to The Documentary Film Book, which I saw in print for the first time when he arrived with book in hand. I am always intrigued with the different histories of documentary, which vary depending on nation (or even locale) from which they originate. To some degree there is an Anglo-American variant but Brian made me realize that as a Brit, he has had to struggle with the hegemonic influence of John Grierson far more than have many American practitioners. (I was exposed to Vertov and Cinema Verité long before I read anything by Grierson.) The discussion got more interesting––and certainly more passionate–– when Brian turned to contemporary documentaries.  He expressed his adamant opposition to The Act of Killing which Joshua Oppenheimer had recently brought to Yale (while I was in Stockholm–see below). So Brian and Josh Glick (then on the cusp of being my former advisee) went toe to toe on this one, while I had to stand by, unable to comment.

He expressed his adamant opposition to The Act of Killing which Joshua Oppenheimer had recently brought to Yale (while I was in Stockholm–see below). So Brian and Josh Glick (then on the cusp of being my former advisee) went toe to toe on this one, while I had to stand by, unable to comment.

Meanwhile undergraduates from my Contemporary Documentary Film and Video class looked on.

****

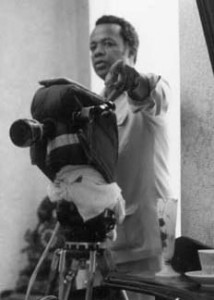

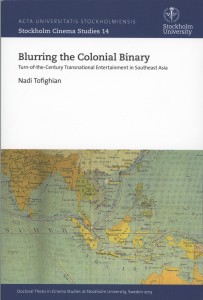

Exhibit C. November 9th. I traveled to Stockholm University to serve as the Opponent for a dissertation defense in Cinema Studies section of the Department of Media Studies: Nadi Tofighian was set to defend his dissertation Blurring the Colonial Binary: Turn-of-the-Century Transnational Entertainment in Southeast Asia. These occasions remain significantly more elaborate rituals than is common in the United States. First, the dissertations are printed. It are real books with an ISPN number (though I have just given you the link to Nadi’s on-line version). So they are definitely more polished than the average dissertation one encounters as a reader in the US. Besides the Opponent who is brought in as a hired gun, there is the Dissertation Advisor (in this case John Fullerton) whose job is essentially over and must sit quietly in the role of silent Proponent. Then there are three evaluators who may ask a question or two at the defense, but they are essentially there to decided the outcome: the choices are either “pass” or “fail.” The process is overseen by a chair, in this case Vice Dean Tytti Soila. After the outcome is announced there is a celebratory champagne toast and lunch for the relevant faculty. That evening the newly approved Doctor of Philosophy puts on a party for friends, family and colleagues. Even the Opponent, who has fortunately failed to convince the jury that the dissertation should be rejected, is invited––and makes a toast.

Exhibit C. November 9th. I traveled to Stockholm University to serve as the Opponent for a dissertation defense in Cinema Studies section of the Department of Media Studies: Nadi Tofighian was set to defend his dissertation Blurring the Colonial Binary: Turn-of-the-Century Transnational Entertainment in Southeast Asia. These occasions remain significantly more elaborate rituals than is common in the United States. First, the dissertations are printed. It are real books with an ISPN number (though I have just given you the link to Nadi’s on-line version). So they are definitely more polished than the average dissertation one encounters as a reader in the US. Besides the Opponent who is brought in as a hired gun, there is the Dissertation Advisor (in this case John Fullerton) whose job is essentially over and must sit quietly in the role of silent Proponent. Then there are three evaluators who may ask a question or two at the defense, but they are essentially there to decided the outcome: the choices are either “pass” or “fail.” The process is overseen by a chair, in this case Vice Dean Tytti Soila. After the outcome is announced there is a celebratory champagne toast and lunch for the relevant faculty. That evening the newly approved Doctor of Philosophy puts on a party for friends, family and colleagues. Even the Opponent, who has fortunately failed to convince the jury that the dissertation should be rejected, is invited––and makes a toast.

In fact, the weekend of events began on Thursday evening when I had dinner with some friends and junior colleagues who were at Stockholm University in the Media Studies Department: Laura Horak had been my advisee as an undergraduate at Yale. She received her Ph.D. from UC-Berkeley and

With Laura Horak, Joel Frykholm, Doron Galili, and Kim Fahlstedt

was at Stockholm as a post-doc. I had met Joel Frykholm when teaching two summers ago at Stockholm University and ended up serving as a respondent for an early cinema panel he organized at the annual SCMS conference last year. I had met Doron Galili when he was a graduate student at University of Chicago. More recently he had been a visiting lecturer at Oberlin College, where he kindly brought me in as a guest scholar-filmmaker. In that small world category he is now a Post Doc at SU. Kim Fahlstedt, who is working on an early cinema dissertation, had been my teaching assistant when I taught at SU two years ago. I could not have survived without his terrific support. So it was a reunion of sorts.

I spent much of Friday preparing and…

Making Coffee before the Defense: John Fullerton and Kim

Pre-meeting Greetings: Stephen Hughes and Tytti Soila

I spent much of Friday preparing and on Saturday went to the Film House where the Cinema Studies Section is based and where the defense was taking place:

Tytti Solia Welcomes

John Fullerton Greets

Nadi in the Hot Seat

Jan Olson Asks a Question

The audience

Congratulations from Mom

…and Dad.

With Nadi’s permission I am presenting my remarks and some accompanying photographs. Once again my camera was working. He began by saying that he plans to revise the dissertation still further and turn it into a book–as well as some articles. My comments, designed to point towards the dissertaiton’s achievements as well as areas for further exploration and analysis, had that in mind. At various moments, Nadi responded to my comments. Those are reflected here, but I have offered Nadi the chance to add comments to this blog (within the blog itself) at some future date.

My Remarks at Nadi Tofighian’s Dissertation Defense

It is a pleasure and an honor to be here to celebrate the defense of Nadi Tofighian’s dissertation Blurring the Colonial Binary: Turn-of-the-Century Transnational Entertainment in Southeast Asia. I would like to thank Vice Dean Tytti Solia, Professor John Fullerton and others in the Department of Media Studies who made this possible.

These rituals are important and I contrast them to ours in the United States, particularly at Yale. The day I left New Haven for Stockholm–Wednesday, we completed the dissertation defense of one of my students—Josh Glick. Four faculty members, including me, had written up our evaluations and comments, which were presented to the American Studies faculty at a lunch time meeting. Dr. Glick’s dissertation was passed. On Monday, Josh thought we were meeting on Tuesday. On Tuesday he learned we were meeting on Wednesday. On Wednesday evening, while waiting for my plane, I filled him in on the results via email. He passed and everyone thought his dissertation would make a swell book with some more revisions. Josh found the process rather anti-climatic. Here at Stockholm University Nadi presents us with a completed book, and it is fair to say that he will not be waiting around for an email to find out if he passed or not.

Toasting His Successful Defense

Of course I come to this event in the role of the opponent, who adds the necessary drama and spice to the proceedings. I like to think I was chosen for a few reasons. First, it continues and so enhances my relations with the Department of Media Studies where I taught a course on Media and American Politics two summers ago. Second, I assume that my profile has somehow become sufficiently established, so my readiness to serve as an opponent is well known. That is I have been the friendly opponent of Tom Gunning and cinema of attractions for some 20 years. Tom, as many of you know, has an honorary degree from Stockholm University and is one of my best friends. Of course, there are scholars for whom I have been a strong opponent with whom I am on less friendly terms, but I am confident that Stockholm University has no relations with them! In any case, I anticipate remaining on friendly relations with Nadi after this defense.

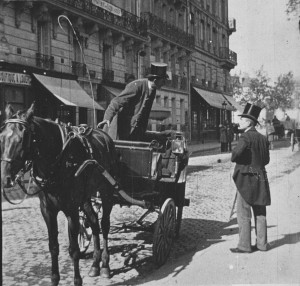

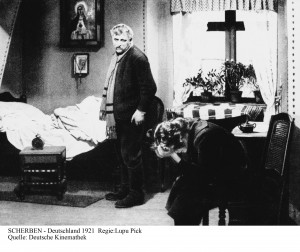

The final reason for my presence today has more to do with my own interests and engagement with the subject of Mr. Tofighian’s dissertation. Indeed, it seems to me that it has much to do with how we first met: at a conference on the Origins of the Cinema in Southeast Asia in Quezon City in August of 2005. Nadi was living in the Philippines completing a master’s thesis on Jose Nepomuceno, who has generally been hailed as the Philippines first native filmmaker. And he gave a paper on the distribution of Nordisk Films in Asia. Most of us, however, were busy pursuing local or national cinemas. For instance in my usual oppositional fashion I was investigating the history of early cinema in the Philippines to about 1912-13 and giving our host and my dear friend Nick Deocampo a hard time of it. Others were looking at cinema practices in Siam/Thailand, Vietnam, Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan and so forth. Each of us was operating within individual “national” silos. So one of the fundamental questions—perhaps the fundamental question––that came out of that conference had to do with the relations and interconnectedness of these different national or proto-national colonial cinemas. In this respect, Nadi’s dissertation is a bold effort to explore this interconnectedness on the level of the transnational circulation of entertainment. He shows how circuses and other amusement entities crossed colonial boundaries as they moved from India and Ceylon into Southeast Asia—Siam, Malaysia, Java, Vietnam and the Philippines. He argues that “Although Southeast Asia as a concept was non-existent, at the turn of the century, it existed as a form of cultural entity, primarily through networks of shipping, trade and cultural amusements.” (p 17) He treats these geographic entities—which have a wildly divergent histories and systems of government as a whole—by examining the impact of transnational entertainments, particularly the cinema, on these societies and the ways they blurred political boundaries. He also emphasizes the blurring of boundaries between colonizers and colonized. With circuses as a precedent, Tofighian argues that the cinema provided an opportunity for diverse racial and economic groups to come together in a shared public space. That is there is a break from previous forms of cultural life, which were strongly segregated along ethnic-racial-cultural lines.

Tofighian must have taken away another insight from the 2005 conference on Origins of the Cinema in Southeast Asia. Our knowledge about Malaysia and particularly Singapore was scant. Because of his work on Scandinavian film in Southeast Asia, he understood Singapore as a pivotal site for commerce in the region and so did extensive, often apparently exhaustive research in newspapers from that city, other Straits Settlements and the Malayan states under British rule. He also did more selective and limited research in newspapers from the Philippines, the Dutch West Indies, Vietnam and Bangkok. It is my impression that many of these materials had not been previously consulted by cinema scholars. Nadi thus uncovered a rich vein of pertinent information and he mined it–-gaining a much better sense of the frequency of exhibitions, the films shown, prices, location and so forth. This is a major achievement and I learned a great deal from it. For instance, the impact of the Russo-Japanese War on Asia in general is something I had not adequately appreciated through my American eyes. It was a war that disrupted the binary, which had European Whites as dominant while Asians occupied lesser positions. Most particularly there was a wave of Japanese film exhibitors who moved into Southeast Asia even as the war was going on––and showed films of this struggle to large audiences in Singapore, the Straits, Bangkok and elsewhere. They represented a New Asia. They were simultaneously promoters of a Pan-Asian sensibility but also of a world in which Japanese occupied a position similar in many ways to European colonizers.

I should add that Nadi utilized an impressive array of secondary literature on the history of British Imperialism and that grounded much of his newspaper research on Singapore. This then was the resource dialectic that informed his intellectual project.

I’d like to develop and explore some other parts of the dissertation in the course of posing some questions but is there anything that you would like to add or correct at this point?

The dissertation does an excellent job of detailing the history of newspapers particularly in Singapore. And they appear in the bibliography. I note you visited the national libraries in quite few countries, but not surprisingly the universe of newspapers in larger than you could exhaust. For instance, my work on early cinema in the Philippines has used the Manila Times which you don’t use—but rather use half a dozen other papers instead. We also live in an era where digitization is more or less rapidly revolutionizing the process of research, particularly newspaper research. Question 1) With the use of newspapers as the backbone of this project, I wonder if Mr. Tafighian could tell us a little bit about this process, its limitations and what perhaps you had to leave unfinished and unsurveyed.

This is my first point of engagement. And I say this as someone who is struggling with the opportunities of our new era of research methodologies. But I think your arguments and insights could have been strengthened by doing a random word access of at least two trade journals—the New York Clipper in the US and The Era in London. For instance I did a random word access of the term “Singapore” in the New York Clipper for 1890-1900 and think I came up with about 40 hits. These included letters from managers of circuses, some of which you mention in your dissertation. Likewise in the Era and the Clipper I received quite a few hits for the magician Carl Hertz, one of the early pioneers of film exhibition in Southeast Asia and someone you mention. He might actually challenge a notion of a cultural Southeast Asia in the 1890s. Hertz first shows films on shipboard headed to Capetown, then stops in South Africa, moved on to India and Ceylon—then Australia and New Zealand before stopping in Java and Singapore. Whether he goes to Manila is unclear—he claims to have been chased out of there by the Spanish American War but did he ever get there? Or did he get there but have to leave before performing? In any case he was in Hong Kong, Nanking, Shanghai and Hawaii before reaching San Francisco.

At the party, Nadi’s sister was the Master of Ceremonies

In short Hertz soon ended up back in London, having completed a round-the-world tour. He demonstrates that there is a level in which we can now talk about the circulation of a global world performance culture; and film complemented and then arguably dominated this circulation. Now there may be other entertainment groups—notably circuses—that move within a more limited geographical boundaries but the manager of Warren’s Circus wrote the NY Clipper from Shanghai and describes performing in Burmah, Ceylon Java, Malaysia, Cochin China, the Philippines, China and Japan. Just as clearly some of the “Australian Letters” suggest a circuit that constructs the British Empire from South Africa to India and Australia and perhaps Hong Kong. So while there are trade routes that bind different parts of Southeast Asia together they also bind its constituent parts together in what might be the orient or the East –while some amusement companies participated in a subset of the global economy, which was the British Empire. This would be particularly true for theatrical companies performing in English. Magicians, circuses and cinema did not have these kinds of constraints. Let me say that as you turn elements of this dissertation into articles and other forms of scholarship, you might also fruitfully perform random word searches of other newspapers such as the London Times, the San Francisco Chronicle.

In any case, the nature of these circuits may change over time. Singapore becomes a regional center for cinema but one that is smaller—connected to the Straits Settlements and Malaysia and to a lesser extent parts of the Dutch West Indies and Siam/Bangkok. Since––as your dissertation points out (pp 138-144)–– Levy Hermanos had offices in the Philippines, those offices rather than its Singapore office probably handled Filipinos’ need for films.

Party Time

2) So my second question is to challenge you and ask you if there is not more work to be done on the complex picture of what constitutes a regional culture—and how this culture is related to a global cultural economy on one hand and to the local on the other.

It seems to me that one important achievement of your dissertation involves explicating how cinema was being used to promote the British Empire and Singapore’s place within it. In the first stage, you argue that cinema is presented as a technological novelty, which is a demonstration of British and European intellectual and technological supremacy. Here you use Brian Larkin’s work on Nigeria (Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria). But you then point out that this technological supremacy more or less rapidly disappears—beginning in the very early 1900s and certainly fully by 1905 when there were the various Japanese Cinematograph exhibitors. So you seem to use Larkin briefly but then suggest that the situation in Southeast Asia is different than Africa.

3) I wonder if you could develop more the difference between West Africa and Southeast Asia. That is, it seems to me that British Colonialism in West Africa versus Southeast Asia (Singapore in particular) were soon different enough so that you might have profitably explored these differences—rather than note a relatively brief moment of similarity and then drop it. That is, if you were to argue for a regional culture with certain characteristics, it would be important to show how this region––Southeast Asia––differs from others. These arguments can be made most readily through comparisons. And such comparisons will inevitably modify any conclusions.

Again Blurring the Colonial Binary is very effective at showing how the cinema was an effective ideological apparatus for the British Empire in Singapore, from the showing of Queen Victoria Jubilee films in 1897 through films of her funeral and King Edward VIII’s coronation and the subsequent Dubar in India. Even the Russo-Japanese War films in which England’s ally—the Japanese—won. But it also seems to me that overall the dissertation exaggerates the homogenization. These films had different resonances in different parts of Southeast Asia. That is, while you offer some new, interesting and valuable information on the cinema in the Philippines, the Philippines was a completely different situation.

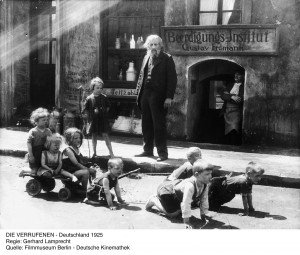

The nickelodeon boom—the rapid proliferation of small, stable and cheap movie theaters—occurred in the United States from mid-1905 to mid 1907. This occurred in Manila in 1902-03—earlier than the US and earlier than elsewhere in Southeast Asia—indeed, it is the earliest example of this phenomenon in the world. How and Why? The end of the Filipino-American War in 1902 produced a rapid expansion of cinematografos or cinemas and other forms of theatrical presentation of motion pictures.[1] Moving pictures quickly found a key role in Manila’s theatrical culture. The names for many of these theaters indicated that they were not extensions of the new American regime but offered an alternative public sphere (to evoke Miriam Hansen).

Film screenings were generally complemented by local theater performances. Their precise nature needs to be better understood since “seditious plays,” usually written in Tagalog by Filipinos who opposed the American occupation, flourished in the 1902-1906 period. In many instances, writers, directors and actors were arrested while some writers were convicted and went to jail for violating the Sedition Act, passed on November 4, 1901.[2] The American colonial government declared,

Until it has been officially proclaimed that a state of war or insurrection against the authority or sovereignty of the United States no longer exits in the Philippine Islands, it shall be unlawful for any person to advance orally or by writing or printing or like methods, the independence of the Philippine Islands, or their separation from the United States whether by peaceable or forcible means or to print, publish or circulate any handbill, newspaper, or publication advocating such independence or separation.[3]

Overall the combination of films and plays suggests a mix of cosmopolitan sophistication that was connected to the French films of Méliès and Pathé and an anti-American, nationalist rhetoric that was tied to the live performances (even if the plays were not explicitly advocating independence) Both acted, at least implicitly, as a rejection of the colonizing power.

Congratulations to the new Doctor

The situation in Singapore was completely different and again, completely different than the situation of the French in Indo China. Singapore did not exist until it became a British port. As Nadi points out, it was a British creation. All of its residence had come from elsewhere within the last 60 or so years or less. People—Chinese, Europeans, Indians, Arabs and so forth went there to work in the city as business and shipping hub. The British Empire provided them with protection. So the situation in Singapore and the Philippines were in most respects—politically and culturally—polar opposites. Likewise we can understand while the present-day Vietnamese government still sees the cinema of the colonial period as fundamentally French cinema—not Vietnamese in any sense. Cinema was not always simply or primarily a technological novelty as it was in Singapore in the outset. If we consider the Lumières’ early film programs in France, they were clearly about three things: Family, State and Nation. The role of family was generally played by the Lumière family, the state was the military and the nation was represented by monuments such as the Champs Elysee or the Eifel Tower. We might note that these were the three terms of the Vichy government in World War II. Lumière programs had a similar configuration in Vietnam. But such early programs had a very different configuration when they were shown in the Philippines—no military scenes, and views from around the world including scenes of Mexico, a former Spanish colony. Filipinos could see themselves as part of an international community that included nations that had won their freedom from Spain. This is of course, implicit.

So this is one of my most serious criticisms. Blurring the Colonial Binary focuses on Singapore—and it seems to me that it situates the cinema there perfectly. But then you homogenize it by tracing, for instance, the issue of musical performances across Southeast Asia or exhibition practices more generally. The dissertation does suggest differences in European/native relations between the Netherlands East Indies but it seems to me that this is the tip of the iceberg. The blurring of colonial binaries—that is, while relations between the colonizer and colonized in Singapore may have been similar in the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong, they must have been different in Bangkok and certainly the Philippines. More on that in a moment, but I thought I should give you a chance to respond to these reservations.

So this is one of my most serious criticisms. Blurring the Colonial Binary focuses on Singapore—and it seems to me that it situates the cinema there perfectly. But then you homogenize it by tracing, for instance, the issue of musical performances across Southeast Asia or exhibition practices more generally. The dissertation does suggest differences in European/native relations between the Netherlands East Indies but it seems to me that this is the tip of the iceberg. The blurring of colonial binaries—that is, while relations between the colonizer and colonized in Singapore may have been similar in the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong, they must have been different in Bangkok and certainly the Philippines. More on that in a moment, but I thought I should give you a chance to respond to these reservations.

Tofighian did his master’s thesis on José Nepomuceno, who made his first films in the late 1910s. In his dissertation, Nadi refers to Nepomuceno as the first Filipino filmmaker. In this regard, I have championed Edward Meyer Gross and his wife and movie star Titay Molina who collaborated on a series of feature films in 1912 and beyond––which is not to downplay the role of Nepomuceno. But a couple of things are worth noting. First Gross and Molina really did blur the binaries of colonized and colonizer in all sorts of ways. He wrote and she starred in a play about Jose Rizal in 1905, before making the filmed version of it in 1912: The Life and Death of Jose Rizal. Nevertheless, Nadi identifies the manager of the Walgraph, Filipino M. E. Quiros as the first person who lived in the Philippines and took films there, including one of a procession in honor of Rizal’s death on December 30, 1904. (pp 211-212) These were often local news films that carried a pro-Filipino and indirectly anti-colonial message.

5) So I wonder, why–– having identified the earliest Filipino filmmaker, you make nothing of it—even bury it in your footnotes. Why?

Even in Singapore, I think there could be a deeper probing of social relations such as the fascinating category of Eurasians, which is an obvious manifestation of blurring boundaries. The term in the Philippines is Mestizo. Here again these blurring of boundaries may well have had different associations and values.

[1] Doreen Fernandez, Palabas: Essays on Philippine Theater History (Ateneo University Press, 1996), 97.

[2] Fernandez, Palabas, 97-103; Vincente L. Rafael, White Love and Other Events in Filipino History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 39-51; Arthur Stanley Riggs, The Filipino Drama [1905] (Manila: Intramuros Administration, 1981), 40-350; Arthur Stanley Riggs, “The Drama of the Filipinos,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 17, No. 67 (Oct. – Dec., 1904), 279-285.

[3] Public Laws Annotated, quoted in Tomas Hernandez, The Emergence of Modern Drama in the Philippines (1898-1912) (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1976), 82.

Finally I put aside my role as Opponent and toast the winner!

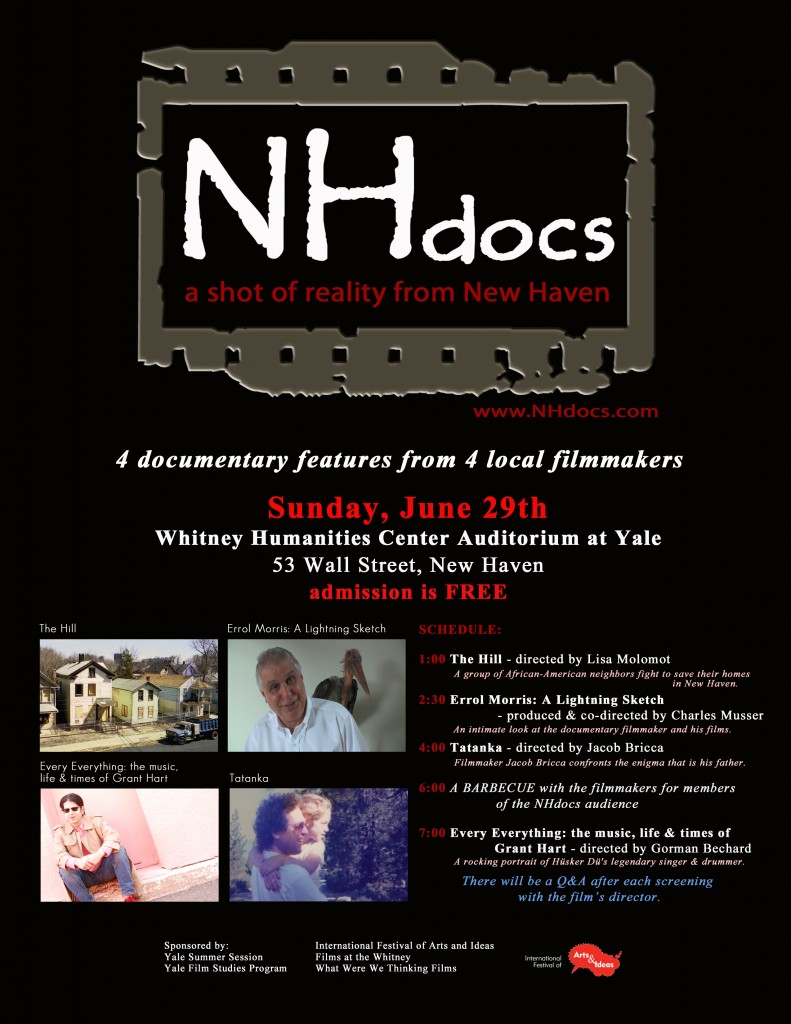

Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch has now been in a couple of festivals and will hopefully be in a few more, but it is always tricky finding an audience or venue.

Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch has now been in a couple of festivals and will hopefully be in a few more, but it is always tricky finding an audience or venue.  I think the film does something that is valuable and worthwhile. It gives certain insights into one of the world’s foremost documentarians and his films. To his credit, there are endless interviews with EM, but shaping them into a narrative–even an attenuated one–is something they can’t do. And while my interview with EM is probably 70% of the film, it is much more than that as well.

I think the film does something that is valuable and worthwhile. It gives certain insights into one of the world’s foremost documentarians and his films. To his credit, there are endless interviews with EM, but shaping them into a narrative–even an attenuated one–is something they can’t do. And while my interview with EM is probably 70% of the film, it is much more than that as well.