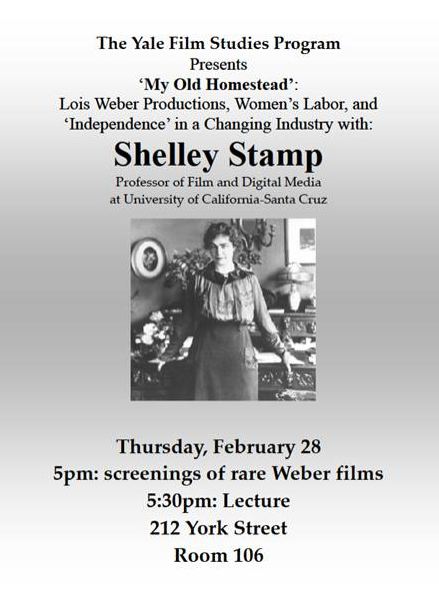

Every other year I teach a required graduate course: Film 603, Historical Methods in Film Study, which focuses on the history of American cinema to 1920–roughly from the beginnings of commercial projection to the establishment of the vertically integrated studio system that constitutes what is generally called the Classical Hollywood Cinema: from the Vitascope to Cecil B. DeMille and Oscar Micheaux. I regularly devote one week to the films of Lois Weber (Suspense, 1913; Shoes, 1916) and Alice Guy Blaché (A House Divided, 1913, Matrimonial Speed Limit, 1913)–as well as to the writings of Shelley Stamp (Movie Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture After the Nickelodeon, and a couple of her essays on Weber). This year we were able to get Shelley to come in person:

Shelley and I have a special relationship that has become clearer over time. It started at NYU in the Department of Cinema Studies, where we both got our Ph.D’s. I had essentially completed my degree by the time she arrived and stayed on to teach as an adjunct–not early cinema but documentary. So we have never been in the same class room –until her visit documented in the above images. If I was working on American early cinema up until about 1909 (when Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company––the dual subjects of my dissertation––parted ways), her scholarship focused on the immediate post-1909 period. Seemingly we were ships passing in the night. Then, as Shelley began to research and write on Lois Weber, our connection became clearer. Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley worked with Porter after he left Edison––at the Rex. As I studied Porter’s career, I came to realize that he almost always worked with a collaborator––whether George S. Fleming, G. M. Anderson, Wallace McCutcheon, J. Searle Dawley or eventually Hugh Ford. (He actively resisted the more hierarchical organizational structures of D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille.) At Rex, Porter found collaborators in Smalley and/or Weber. And when he left Rex in 1912, they stayed on and retained this collaborative manner of working.

As I began to write more about the American cinema of the 1910s, our ships soon came within easy hailing distance on a calm sunny day. I eventually wrote about another husband-wife team of filmmakers: Herbert and Alice Guy Blaché. The success and eventual breakdown of the Smalleys and the Blachés as filmmaking teams coincided very closely. These couples were at their professional best between roughly 1912 and 1916, after which their relationships rapidly deteriorated. Both marriages ended in divorce around 1922. However, Shelley’s and my historical approaches share something more than subject matter–it involves a theoretical or methodological orientation which is instinctive dialectical.

Let me reveal a small secret. Typically I show students Traffic in Souls (Tucker, 1913) and have them read Lee Grieveson’s Policing Cinema, which views the 1910s as a period of increasing social and cultural regimentation–a narrowing of what is possible. Lee finds the kinds of debates and state interventions around Traffic in Souls and other white slave films to be exemplary of this policing of cinema. His approach is explicitly indebted to Michel Foucault. Now Lee is an outstanding researcher and I admire the force of his arguments. Yet I find myself aligned with Shelley’s position when she remarks

Negotiating a place for female viewers within cinema’s imaginary topography was made all the more troubling by the vice pictures: their sexually frank subject matter was assumed to repulse women, yet observers could not ignore women’s evident attraction to the material. The way that cinema enable a fictive remapping of a viewer’s relation to social space––although potentially liberating for women––was for the same reason threatening to any commentators. Now an industry actively courting female patronage also had to consider the implications of female spectatorship. Indeed, the white slave film controversy shows an industry grappling with the distinction between the characterization of cinema’s social audience and the various spectatorial positions that it offered (Movie Struck Girls, p 94).

This is the kind of film history (or media history) to which both me and my students should aspire. At a moment when the Woman’s Suffrage Movement was transforming the social and political landscape, cinema gave women virtual access (however diluted and sensationalized) to a formally inaccessible realm.

After our class meeting, Shelley screened a few hard-to-see Weber films and gave a public presentation:

Later we traded stories about something else we have in common: the ways that administration and family have retarded the completion of various book projects.