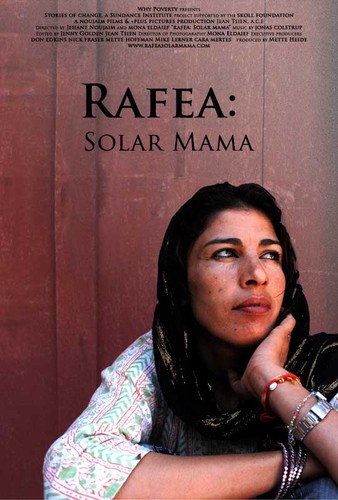

It’s been an interesting week. I’ll spare you the details except for my experience of two radically different screenings involving two sets of very different filmmakers. Due to the snow storm, Yale cancelled classes on Monday and Tuesday and provided me with the opportunity to run into the city and see Jehane Noujaim and Mona Eldaief’s new film Rafea: Solar Moma (2012) at Stranger than Fiction/IFC.

Of course, they were there for a Q & A afterwards:

Of course, they were there for a Q & A afterwards:

In fact, their editor Jean Tsein joined them on stage, while various producers and crew were in the audience. It was an all-women support team.

The website for Rafea gives a bare bones description:

Rafea is a Bedouin woman who lives with her daughters in one of Jordan’s poorest desert villages on the Iraqi border.

She is given a chance to travel to India to attend the Barefoot College, where illiterate grandmothers from around the world are trained in 6 months to be solar engineers. If Rafea succeeds, she will be able to electrify her village, train more engineers, and provide for her daughters.

Rafea has the ability, confidence and determination to pull it off, but her husband continually tries to sabotage her efforts. One feels it from the film itself, and it was openly acknowledged by Noujaim and Eldaief: the filmmakers’ presence and even their active intervention on Rafea’s behalf enabled her to persevere and thus provide the film with its tentatively upbeat outcome. This is Third World Feminism in action. The solidarity involves those in front of the camera with those behind it. Noujaim and Eldaief help Rafea deflect her husband’s jealousy at her growing independence and sense of purpose. His threats of divorce––which would mean taking her children (all daughters) away from her–are less and less credible. Nevertheless, one has a sense that the film’s modestly uplifting conclusion may be difficult, perhaps even impossible, to sustain.

There are ways in which Rafea: Solar Mama has the quality of a reality TV program in which impoverished, illiterate women from all over the world are selected and brought together at a distant locale, then given a chance to escape poverty against long odds. And nowhere do these odds seem longer than among a poor Bedouin village in Jordan. Yet the filmmakers’ activism as well as their persistence and filmmaking talents are essential parts of this story. One should note that these co-directors are Egyptian-born women who undoubtedly faced related challenges and exemplify the possibilities of sucess. Carol Chazin, who was in the audience, remarked after the screening that it reminded her of Barbara Kopple and Harlan County--that is an important moment of feminist breakthrough in the documentary field that happened some 40 years ago.

At the opposite end of the cinematic spectrum is Ken Jacobs and his Nervous Magic Lantern performance which he and his wife Flo Jacobs presented at Yale as part of a graduate student conference entitled Expanded Cinema.

His short before the Nervous Magic Lantern was The Green Mile (2011), a five-minute tour de force that played with vision and made clear the ways in which digital media has liberated certain kinds of so-called experimental filmmaking. What was once done painstakingly on an optical projector with all the challenges of multi-generational printing have been solved. The picture is pristine and aggressive in the way it challenges us to think about optical illusions and perception more generally.

In some respects, The Green Wave is part of a genre of experimental film that goes back, at least, to Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1965) with its aggressive assault on the spectator. Conrad’s film begins with this title card:

WARNING. The producer, distributor, and exhibitors waive all liability for physical or mental injury possibly caused by the motion picture “The Flicker.” Since this film may induce epileptic seizures or produce mild symptoms of shock treatment in certain persons, you are cautioned to remain in the theatre only at your own risk. A physician should be in attendance.

With The Green Wave, I found myself engaged in an optical challenge that was caught between intellectual fascination and physical pain. This was only intensified with the Nervous Magic Lantern, which Ken and Flo used to present the piece Times Squared. The sound track was an audio recording that Ken made as he moved through the subway system, starting at Times Square. The piece starts with a simple play of light on the screen that suggests the strobe effect one often encounters on the subway. The exhibition then turns to the projection of “smudges” (Ken’s words) that have a powerful 3-D effect as well as a sense of motion and depth.

Again I found myself torn between a fascination with what I was seeing–the illusion of motion, the false sense of 3-D––and the visceral sense of being under assault.

The Whitney Humanities Center Auditorium was full–standing room only, and the Film Studies faculty were there in force. I was sitting next to Brigitte Peucker who suggested that the piece might better be called “Torture the Spectator” and made an exit. She was not alone. I sympathized but decided to stay. Others, like me, found ourselves simply closing our eyes at moments. One way or the other the visual experience was being etched into our retina and nervous system to the point that I continued to feel its after effects all weekend. Ken characterized the sensation produced by his Nervous Magic Lantern as ecstasy, which is perhaps one reason why not a few people called him the Madman of the Cinema (always in a tone that conveys respect, wonder and appreciation, I should add).

When asked, Ken saw the Nervous Magic Lantern generating a powerful tension between the audio and the visual. “The sound is gravity,” he asserted the the Q & A. “The image is crazy, liberating.” This allowed for individual, nonstandardized responses. Certainly the sound track is readily accessible and and offers an apparently simple audio record of movement through the subway. As a long-time New Yorker, I have had a wide-range of reactions to, sensations of and experiences in the subway. Some are very much along the lines of D.A. Pennebaker’s Daybreak Express (1958). There are times when the subway is a delight, when I am never happier to be a New Yorker as I am wisked through the city via this transportation system used by all the city’s denizens, from Wall Street brokers to the homeless. I feel that the subway, populated by peoples whose roots are from all over the world, is almost my second home. But there are other moments, often late at night when I have descended into the subway and felt I was descending into a hellish world of too bright florescent light. The light pierces my eyes and the people seem remote, foreboding–– as if one has taken a bad trip. That is the feeling I had watching Times Squared. It made me wonder what my reaction would be to Jacob’s Celestial Subway Lines/Salvaging Noise (2005), a somewhat similar performance using “This is accompanied by industrial sound and music provided by John Zorn and Ikue Mori.”

Afterwards Ken participated in a Q & A:

Ken repeatedly emphasized his debt and inspiration to abstract expressionist Hans Hoffmann (1880-1966). “His works gave me horrible standards to live up to.” He’d encounter Hoffman in the village: “I considered myself unworthy of speaking to him.” And yet he did–though never mentioning his interest in film except on one occasion when he “stupidly” told Hoffmann that he was working with film and that “I think film is the art form of the century.”

A critic on WetCanvas suggested some ways in which Hans Hofman’s paintings directly inspired Jacobs:

Hofmann believed fervently that a modern artist must remain faithful to the flatness of the canvas support. To suggest depth and movement in the picture – to create what he called “push and pull” in the image – artists should create contrasts of color, form, and texture.

Nature was the origin of art, Hofmann believed, and no matter how abstract his pictures seemed to become, he always sought to maintain in them a link to the world of objects. Even when his canvases seemed to be only collections of forms and colors, Hofmann argued that they still contained the suggestion of movement – and movement was the pulse of nature.

These became Jacobs’ preoccupations as well.

Asked “What cinema is?” Ken immediately replied that “Cinema is thought.” At the same time he finds in cinema both an erotic fascination and an intellectual fascination. If one substitutes the term “somatic” or perhaps “optical” for “erotic”–it might be easier to accept but it also feels as if Jacobs’ passion for what he shows us has a strong erotic or visceral component for him.

Ken Jacobs also distributed “Notes for a Nervous Magic Lantern Performance.” I asked him if I could add them to this blog and he agreed. So here they are: