I commend and appreciate my compatriots at the Giornate del Cinema Muto who blog about the films at the end of each day––people like Pamela Hutchinson with her blog Silent London. (Many also use Facebook.) For better or worse, I seem to spend that extra time at the Posta bar across the street. Nevertheless, I feel compelled to offer some kind of response to these eight days of intensive, delightful immersion (October 5-12, 2013).

Unfortunately for the second Giorante in a row, my still camera failed (last year it had just been stolen, this year the battery had stopped taking a charge). So I am relying on images liberated from the Giornate’s websites.

First my public thanks to all those who made this possible–starting with David Francis, Livio Jacob, Piera Patat (aka Saint Piera), Paolo Cherchi Usai …and the list goes on. The festival has never been better.

I could not help but notice that for the second or third year in a row, I was the only Yale faculty member in attendance. So this post began as an email addressed to my departmental colleagues, written largely on the plane home. Here it is–more or less–with some added images.

Dear Colleagues,

It is always a challenge to capture the essentials of the Giornate del Cinema Muto.  Since I thought of you many times over the eight days that I was in Pordenone, I decided to offer you a quick (if lengthy) summary. It is impossible to escape a sense of anxiety if not guilt for taking a week’s sequester in the middle of the semester. I always wonder if it is justified for all sorts of reasons, not just in terms of teaching but leaving the family for 10 days. Nevertheless, with Silent Cinema an essential part of my portfolio (ie teaching Film Historiography to grad students who are joint with many different departments), each year I come away convinced that this once-a-year crash course is essential if I am to stay up to date. So…

Since I thought of you many times over the eight days that I was in Pordenone, I decided to offer you a quick (if lengthy) summary. It is impossible to escape a sense of anxiety if not guilt for taking a week’s sequester in the middle of the semester. I always wonder if it is justified for all sorts of reasons, not just in terms of teaching but leaving the family for 10 days. Nevertheless, with Silent Cinema an essential part of my portfolio (ie teaching Film Historiography to grad students who are joint with many different departments), each year I come away convinced that this once-a-year crash course is essential if I am to stay up to date. So…

You can barely see me having “dinner” with Kevin Brownlow–an ice cream while we stand in line for the world premiere of film material from Orson Welles’ Too Much Johnson

There were faculty from every major graduate program at Pordenone: Yuri Tsivian (Chicago), Linda Williams, Anne Nesbitt, Tony Kaes (UC-Berkeley), Allie Fields (UCLA), Laura Serna (USC), Dan Streible (NYU), Richard Abel, Giorgio Bertellini (Michigan). Phil Rosen did not show and there was no one from Harvard; but there were many profs from other US universities (Richard Koszarski, Peter Lehman and Tami Williams who received tenure on the fourth day of the festival, etc.) Obviously universities from around the world were well represented. I had dinner with Ian Christie, Vanessa Toulmin, Christine Gledhill, Kevin Brownlow (who is definitely not at a university), Ansje Van Buesekom–lunch with Andre Gaudreault and Martin Loiperdinger. I spent time with John Fullerton and various students from Stockholm University where I taught two summers ago. Of course there were lots of graduate students there from the US, including our own Danny Fairfax. Yale Film Studies major Laura Horak, who got her Ph.D. from UC-Berkeley and has a post-doc at Stockholm University, was there: she was just hired for a tenure track job at Carleton University. Of course, many film archivists attended: not only Paolo Cherchi Usai but Pat Loughney (despite the US government shut down). Chris Horak (UCLA Film & Television Archives) and Brian Meacham (Yale Film Study Center) missed this year but will hopefully be there next. (Brian wrote at least one of the program notes.)

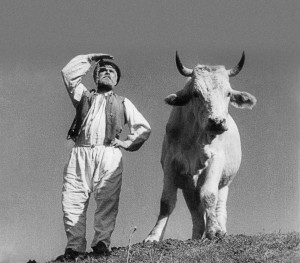

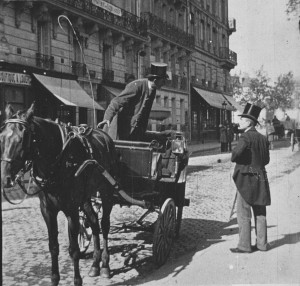

It was a wonderful festival this year. For me, the high point was perhaps the screenings of some 70 films that were made for the Cinematographe Joly-Normandin in 1896-97. I had known about the Cinematographe Joly, which was a French machine that was exploited in the US by Eberhard Schneider at the Eden Musee. However, I had thought it was just another version of the standard 35mm projector, like R. W. Paul’s Animatograpahe. In fact, it was a five sprocket 35mm system which created a different shaped image. Only films taken for the Cinematographe Joly could be shown on it (and vice versa). So it had much in common with the Lumière Cinematographe, the Biograph system or Gaumont’s 60mm film system. This was really a surprise and requires some adjustments in grasping the cinema landscape of the novelty period. (The Cinematographe Joly was indirectly involved in the Charity Bazaar Fire in Paris of 1897.) Camille Blot-Wellens, who curated the program, has also written a 200-page study of the company and system. It is being published in Spanish on the Internet but it seems important to have her effort in a language more of us can read, so I put her in touch with John Libbey who seems ready to publish an English language version.

It was a wonderful festival this year. For me, the high point was perhaps the screenings of some 70 films that were made for the Cinematographe Joly-Normandin in 1896-97. I had known about the Cinematographe Joly, which was a French machine that was exploited in the US by Eberhard Schneider at the Eden Musee. However, I had thought it was just another version of the standard 35mm projector, like R. W. Paul’s Animatograpahe. In fact, it was a five sprocket 35mm system which created a different shaped image. Only films taken for the Cinematographe Joly could be shown on it (and vice versa). So it had much in common with the Lumière Cinematographe, the Biograph system or Gaumont’s 60mm film system. This was really a surprise and requires some adjustments in grasping the cinema landscape of the novelty period. (The Cinematographe Joly was indirectly involved in the Charity Bazaar Fire in Paris of 1897.) Camille Blot-Wellens, who curated the program, has also written a 200-page study of the company and system. It is being published in Spanish on the Internet but it seems important to have her effort in a language more of us can read, so I put her in touch with John Libbey who seems ready to publish an English language version.

Then there was a Lubin film: The New Operator (1911). It was preserved by Lobster Films and is something I now plan to show in my Hollywood Novel, Hollywood Film course since Serge Bromberg has offered to send me a file. A novice cameraman is hired by the Lubin Studio and tries to shoot a variety of scenes (including a Kiss scene), all of which end in disaster.

Likewise Hollywood Snapshots, taken in Hollywood in 1922, in which a Rube comes to Hollywood to witness all the scandal he had hear about. His expectations are repeatedly dashed. These were obviously my territory, but…

I thought of Katie Trumpener quite a bit as I followed the strand Sealed Lips: Sweden’s Forgotten Years. Katie has just taught a course on Swedish cinema and was in Sweden this past summer. We would have had a lot to talked about. Director Gustaf Molander was very much in control of material in films such as Hans Engelska Fru (Matrimony/ Discord). A British widow, played by Lil Dagover (this was a Swedish/German co-production), must again marry for money–specifically a Swedish lumber king who has come into possession of her family’s debt–and so save the family from ruin. With many twists and unexpected turns it all worksout but the process of getting there is remarkable.

A film set in the seafaring world, Den Starkaste (The Strongest,1929), spent much of its time in the unfamiliar world of polar ice. There is a rescue scene in which the protagonist races from ice flow to ice flow that far exceeds the scene it evokes––from Way Down East.

One film I particularly enjoyed was Sweden’s first feature sound film: Konstgjorda Svensson (Artificial Svensson). It has an ironic, somewhat absurdist take on technology–including the technology of the sound film. Swedish comedian Fridolf Rhudin plays Svensson, an inventor of Rube Goldberg-like devices. The film begins with a intimately romantic embrace between him and a woman, which Rhudin (who has been doing the kissing) interrupts in order to deliver a speech about the sound film, which is reminiscent of Will Hays’ intro to the Vitaphone program. As someone whose face is so expressive, he waxes eloquently about his dilemma–even evoking Shakespeare (“the silent film or the sound film, that is the question”). And there are musical sequences inserted at several points in the film––mostly of banjo playing. Svensson’s rival is a skilled banjo player and we get a sync version of that, again very much like a Vitaphone insert from The Jazz Singer. Then Svensson, whose banjo efforts are total failures, sings and plays while faking sync to a record. A second effort to fake sync has him play the banjo and lip-syc as a full orchestra accompanies the singer. Svensson, who had also invented ways to avoid army service, finds himself in love with the daughter of a colonel. And he ends up joining the army as a stand-in for his best friend who needs some extra days to chase a girl. So it is an army farce a la Jean Renoir’s Tire au Flanc. These are must see films in the Swedish canon I think!

There were also some Czech films built around the movie star Anny Ondra but I found their light comedy to be light-weight and used them for breaks at a certain point.

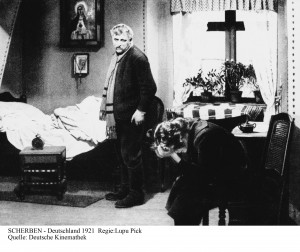

For Brigitte Peucker, who periodically teaches a course on Weimar Cinema, the German films were also fascinating.  There was Lupa Pick’s Shattered (1921), in which an inspector comes to an isolated railway station and seduces/rapes the daughter of the station master, which destroys the family and leaves the daughter alone, vulnerable and desperate. It is an expressionistic film, stripped of subplots, combining slow or almost death-like acting with expressionist lighting.

There was Lupa Pick’s Shattered (1921), in which an inspector comes to an isolated railway station and seduces/rapes the daughter of the station master, which destroys the family and leaves the daughter alone, vulnerable and desperate. It is an expressionistic film, stripped of subplots, combining slow or almost death-like acting with expressionist lighting.

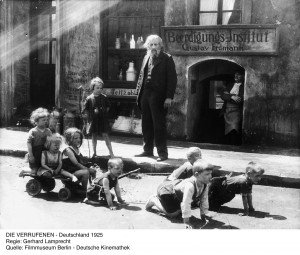

The most interesting group of films were by Gerhard Lamprecht (1897-1974), which dealt with the underbelly of Berlin life in ways that are powerful. Die Verrufenen (1925, The Outcasts, released in The US as The Slums of Berlin) follows a man who is released from prison for perjury (he says almost nothing about his crime until late in the film when he says that sometimes perjury is necessary to retain one’s honor). Rejected by his father and his fiancée and unable to get a job, he attempts suicide only to be rescued by Emma, a streetwalker. The whole plot is given in the film notes of the Giornate’s fabulous catalog, but it is the small details and moments that make this film so moving. For instance, he spends a night at a facility for the homeless where someone tells him where he can get some work sewing. Finally a job! They go together and at the end of the day, he discovers that payment in only in the form of cheap vodka or the like. That’s enough for his alcoholic compatriots. In Die Unehelichen (1926, Illegitimate Children aka Children of No Importance), their illegitimacy is never actually mentioned until late in the film. As with The Outcasts, it is a way of exposing social inequities. So there is a didactic quality at moments but with a humanistic eye that is kept at sufficient distance so it seems to escape sentimentality. Three children of no importance are in a household where the man is an abusive drunkard and the wife scrimps on the money she is given to care for them. One girl gets sick and the wife does not bring in a doctor until the girl’s case has become so extreme that she dies. Another girl ends up in the countryside with a miller’s family. The older boy is first rescued by a well-to-do woman but then his father appears and he is taken to work on a barge. Only when he tries to drown himself does his father realize he can’t be used for heavy labor and let’s him go. Apparently the Communist Party found the film too concerned with individuals rather than mapping out the whole social problem in a way that would call for radical action. From this hard left viewpoint there was a huge gap between these stories and the actual circumstances of the many, many children in this condition. Outrage, however, strikes me as fundamental to the film, just subsumed. The happy outcomes seem obviously atypical. My own reaction was that films along these lines should be made in the US today. In today’s environment, they would surely be seen as quite radical. Lamprecht stayed in Germany throughout the war where he continued to direct, but nothing that –from the little available on the web–seems like Nazi propaganda. And he made at least one rubble film after the war. So I’d like to know more about him.

The most interesting group of films were by Gerhard Lamprecht (1897-1974), which dealt with the underbelly of Berlin life in ways that are powerful. Die Verrufenen (1925, The Outcasts, released in The US as The Slums of Berlin) follows a man who is released from prison for perjury (he says almost nothing about his crime until late in the film when he says that sometimes perjury is necessary to retain one’s honor). Rejected by his father and his fiancée and unable to get a job, he attempts suicide only to be rescued by Emma, a streetwalker. The whole plot is given in the film notes of the Giornate’s fabulous catalog, but it is the small details and moments that make this film so moving. For instance, he spends a night at a facility for the homeless where someone tells him where he can get some work sewing. Finally a job! They go together and at the end of the day, he discovers that payment in only in the form of cheap vodka or the like. That’s enough for his alcoholic compatriots. In Die Unehelichen (1926, Illegitimate Children aka Children of No Importance), their illegitimacy is never actually mentioned until late in the film. As with The Outcasts, it is a way of exposing social inequities. So there is a didactic quality at moments but with a humanistic eye that is kept at sufficient distance so it seems to escape sentimentality. Three children of no importance are in a household where the man is an abusive drunkard and the wife scrimps on the money she is given to care for them. One girl gets sick and the wife does not bring in a doctor until the girl’s case has become so extreme that she dies. Another girl ends up in the countryside with a miller’s family. The older boy is first rescued by a well-to-do woman but then his father appears and he is taken to work on a barge. Only when he tries to drown himself does his father realize he can’t be used for heavy labor and let’s him go. Apparently the Communist Party found the film too concerned with individuals rather than mapping out the whole social problem in a way that would call for radical action. From this hard left viewpoint there was a huge gap between these stories and the actual circumstances of the many, many children in this condition. Outrage, however, strikes me as fundamental to the film, just subsumed. The happy outcomes seem obviously atypical. My own reaction was that films along these lines should be made in the US today. In today’s environment, they would surely be seen as quite radical. Lamprecht stayed in Germany throughout the war where he continued to direct, but nothing that –from the little available on the web–seems like Nazi propaganda. And he made at least one rubble film after the war. So I’d like to know more about him.

Another Lamprecht film, Menschen Untereinander (1926, People Among Each Other) followed the different lives of people living in an apartment building. Characters are astutely drawn and the desperation that many face is revealed. Nevertheless, all turns out well in the end for all except those who deserve to be punished. It is impressive ensemble acting in which there are no stars–not unlike some of Renoir’s films. Particularly with its endings, the film seems too neat, too pat as if the building becomes a utopian refuge due in part to interventions of the daughter of the jeweler who occupies the ground floor.  Perhaps Unter der Laterne (1928, Under the Lantern) was my favorite. A woman is kicked out of the house by her overly strict and unforgiving father. With a way station in cabaret, she is hounded by her father who wants to institutionalize her, forcing her into the underground with a new identity, followed by prostitution and death. Apparently these will be coming out as a DVD set but it was great to see them on the big screen.

Perhaps Unter der Laterne (1928, Under the Lantern) was my favorite. A woman is kicked out of the house by her overly strict and unforgiving father. With a way station in cabaret, she is hounded by her father who wants to institutionalize her, forcing her into the underground with a new identity, followed by prostitution and death. Apparently these will be coming out as a DVD set but it was great to see them on the big screen.

And then for our Japanese film sensi––Prof Aaron Gerow. After a heavy Japanese program last year, there was little that was offered this year. One of the high points was a benshi performance by Ichiro Kataoka, a student of Midori Sawato, whom I had written about many years ago after my first visit to Japan with Before the Nickelodeon. Billed as “Japan’s charismatic new star benshi,” he accompanied fragments of two Samuri films starring Denjiro Okochi.

For John MacKay and Katy Clark, whose courses include ones on Russian and Soviet film: a major strand of the festival involved Russian and Ukrainian films. In particular, many of us discovered there was a Mother before Pudovkin’s Mother. If it was an influence, it was only to show what should not be done or should be totally reconceived. (There was also a trailer for Vertov’s The Eleventh Year!) The importance of Pudovkin’s Mother was obvious in several Ukranian films about young revolutionaries and their more conservative parents who only change their political stripes after their children have been brutally killed by the forces of reaction.

Dva Dni (1927, Two Days) was one of my favorites in the festival. A family abandons its country estate during the Civil War as the Red Army approaches. The loyal caretaker, who is to told to bury the family silver, is left behind to protect what he can. It turns out that the head of the red detachment is his son, who obviously does not share his politics. Their meeting is awkward. Then the adolescent son of the landed gentry shows up, having been separated from his family. The caretaker hides him and protects him. When the Red army temporarily retreats, the caretaker’s son is told to stay behind. The landlord’s son then turns him over to the white army, and he is soon executed. Now the father starts a fire in the palatial abode and locks the doors: the white army generals, the gentry’s son and the entire mansion burn to the ground.

Other films, including Dovzhenko’s Khlib (Bread, 1929)–shown at the festival with several other Dovzhenko films, follow a similar pattern. Another affecting example would be Nichnyi Viznyk (1929, The Night Coachman). These are just a reminder of the profound influence of Pudovkin’s masterpiece.

There were also some interesting if minor Georgian films such as Dilis Ati Tsuti (1931, Ten Minutes in the Morning) which argues that exercise is need to counter the adverse effects of labor on the body. It seemed positively Vertovian in its inspiration. Moreover, there was a good sampling of Soviet animation films from the 1920s, many of which reminded me of Vertov’s Soviet Toys. This was certainly true for Durman Demiana (1925, Demain’s Drug), made by one of his collaborators. If I am keeping titles and films straight, this short borrowed a Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend story line and used it for political ends: the counter-revolutionary is an alcoholic. Other animated films such as Interplanetary Revolution (1924) were astonishing.

Dudley Andrew: Alas, the French films were all outside your period in that the were made before 1910. There were two recent documentaries, however: Mussidora, la dixieme muse and Natan–The Untold Story of French Cinema’s Forgotten Genius (2013).

Penny Marcus & Francesco Casetti: There were some Italian silents but most of them were shown at times that did not work for me–a symptom of the very full program this year.  However, the major book of the festival was Giorgio Bertellini’s Italian Cinema: A Reader (2013), for which I provided a blurb at the last minute:

However, the major book of the festival was Giorgio Bertellini’s Italian Cinema: A Reader (2013), for which I provided a blurb at the last minute:

From Giorgio Bertellini’s brilliant introduction, which provides a compelling framework for re-evaluating Italian silent cinema, to the final essays, which invite the reader to become an active explorer of this rich cultural heritage, Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader offers a compelling, multi-faceted matrix for all those ready to grapple seriously with a crucial national cinema of the silent era. Most importantly, its many insights into Italian film culture necessarily require a reevaluation of French, American and other European cinemas of the silent era and alter our understandings of the ways early cinema embodied conceptions of modernity.–Charles Musser, Yale University

Giorgio seemed quite happy with it!

For my fellow Americanists J.D. Connor, Ron Gregg and Michael Kerbel: Viewing those films within our area of specialization was not too painful. William Wellman’s Beggars of Life (1928) featured the always fabulous Louise Brooks while Richard Arlen kept up his end when it came to exuding sexuality. Wallace Berry wasn’t too shoddy either. It was a preview of the depression to come. A couple on the lam, riding the rails with the tramps. And every one of them would like a little action with Louise Brooks. Wellman’s film, made right after Wings, it was a great way to start the festival.

Of course the coup of the festival was a world premiere of Orson Welles’ Too Much Johnson. It constituted a feature length’s worth of material shot to be integrated into the comedic play Too Much Johnson that Welles was directing (ca 1938). The integration never happened, but Citizen Kane certainly did not come out of nowhere. The film, over cranked and silent, was made by someone who already possessed a sense of cinematic possibilities. Among the film’s many treats: Welles’s use of space and and the young Joseph Cotton showing potential as a comedian.

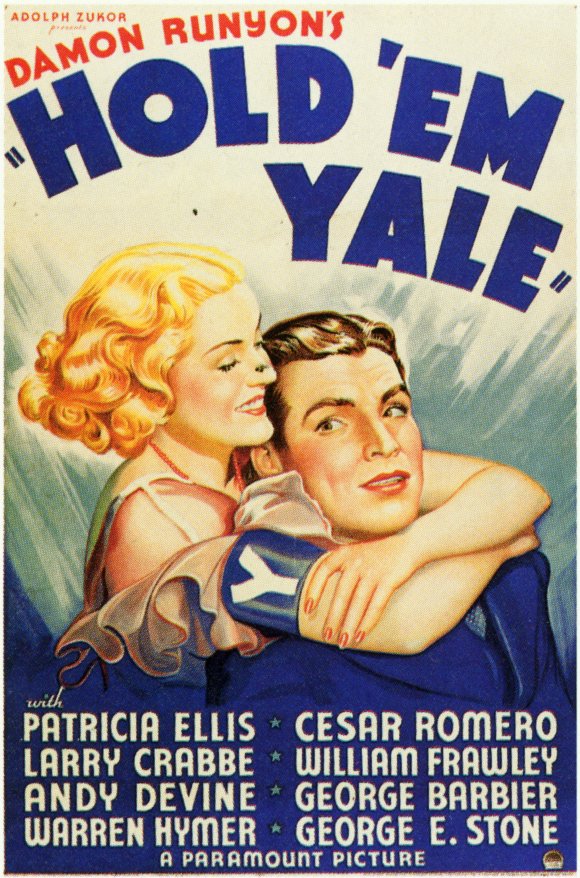

And then there was a film for the entire Yale faculty–not just those in Film Studies: Hold ’em Yale (1928), an insightful assessment of student priorities during the mid 1920s. Certainly it reminds us, claims to the contrary, that the amount of time that students spent hitting the books may have been even more limited in the past than it is today. One might conclude that there is no grade inflation, after looking at this picture. If these students got gentlemen’s C’s, our students deserve the A- average they have come to expect. A major claim to fame for Hold ’em Yale is that it was the first film in which the new Yale Bowl appears. I think Brian Meacham mentioned that we might soon have a chance to look at this film in the WHC Auditorium.

And then there was a film for the entire Yale faculty–not just those in Film Studies: Hold ’em Yale (1928), an insightful assessment of student priorities during the mid 1920s. Certainly it reminds us, claims to the contrary, that the amount of time that students spent hitting the books may have been even more limited in the past than it is today. One might conclude that there is no grade inflation, after looking at this picture. If these students got gentlemen’s C’s, our students deserve the A- average they have come to expect. A major claim to fame for Hold ’em Yale is that it was the first film in which the new Yale Bowl appears. I think Brian Meacham mentioned that we might soon have a chance to look at this film in the WHC Auditorium.

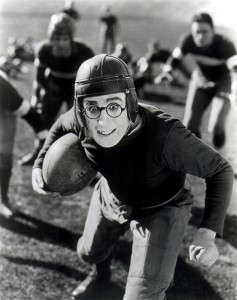

If so, it might be worth taking a cue from the Giornate which effectively paired the film with Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman (1925). You may remember a passage in Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run?, in which Sammy Glick is watching a bunch of football pictures to see what ideas he can steal. The producers of Hold ’em Yale were early Sammy prototypes. who only bothered to see one college picture before making Hold ’em Yale–and it was Lloyd’s.

Anyway I thought I should give a brief report and also remind you that there are lots of reasons for you, my dear colleagues to attend. I am ready to hold the academic line for Yale in this regard, but really this should be a team sport!

best,