Have Errol Morris and Chris Choy ever met? Their personal and cinematic styles are so extraordinarily different, it is almost hard to imagine; and yet they both made ground-breaking, innovative courtroom documentaries ca. 1988, which profoundly contributed to the revitalization of documentary practice in the United States: Chris’s Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1987, with Renee Tajima-Peña) and Errol’s The Thin Blue Line (1988). Both films are audacious, inspirational and ultimately complementary. On an obvious level, everyone agrees that Ronald Ebens killed Vincent Chin: there were numerous eyewitnesses and Ebens himself confessed. For that crime, he received nothing more than probation. If the immediate answer to the film’s title is obvious, a search for deeper answers is far more troubling. In contrast, Randall Adams was convicted of murdering a police officer and faced death until The Thin Blue Line effectively proved that Adams was innocent and identified the actual killer. Yin and Yang. I wrote about both these films in an essay: “Film Truth, Documentary and the Law: Justice at the Margins,” University of San Francisco Law Review 30:4 (Summer 1996), 963-984. (At present it seems to be available on line here.)

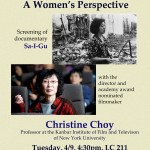

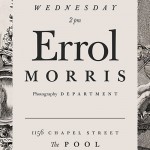

I can’t take any credit for this, but a mere eight days separated their recent visits to Yale. Chris showed her documentary Sa-I-Gu (1993) about the experience of Korean women (mostly small business owners) during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots/Rebellion that was sparked by the Rodney King trial–-and excerpts of forthcoming effort that re-examines that upheaval some 20 years later. Sa-I-Gu shares a recurrent theme with her other documentaries: Asian Americans have to stop acting like a model minority and stand up for their rights! For his presentation at the Art School, Errol returned to The Thin Blue Line and the noir films of the 1940s and early 1950s that inspired him.

One thing for sure. Until very recently I avoided those posed portraits of eager scholar and famous filmmaker. They have always seemed slightly tacky. I’ve known both Errol and Chris for more than 20 years but never requested a photo op from either one. Obviously, that has just changed. The public diary, narcissistic ruminations and inevitable self-promotion of this website is certainly one explanation. But it also has something to do with the rapid passage of time and being ready to document at least one instance in our associations. So somewhat shamelessly here they are–along with the posters for Chris and Errol’s visits:

As readers of my website know, I have been working on a documentary: Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch (2013). It’s been shown as a work in progress at several universities and even a few odd classes largely devoted to documentary. It all came about because my own failed efforts to get Errol down to Yale. Fate had something else in mind: a backdoor documentary. Carina Tautu and I went up to his Cambridge offices to record a conversation with Errol and bring it back down to show at a festival of his films, which I programmed. The rest, as they say, is history–or friendly persistence on my side and a certain graciousness on Errol’s. Since our visit, he has made two appearance on the Yale campus– under someone else’s auspices. Once again this has all been to the good. I haven’t had to worry about hosting and both times showed up at his events with video camera in hand. My goal has simply been to have some kind of lasting record of his speculations on cinema and the nature of our universe. In fact, Errol asked his hosts at the Art School if someone could record his conversation as he was walking into the “pool.” So I quickly solved that problem. I could easily begin to see this as one of my responsibilities.

Among the various high points of his talk, Errol shared his “Fuck You Theory of Art” with the MFA art students, where he had a ready audience. In a way, many of the filmmakers that have fascinated me practice this in some shape or form. Chaplin–for sure. Oscar Micheaux–certainly. No filmmaker has ever made a film that said “Fuck You” to his star more than Micheaux did to Paul Robeson in Body and Soul (1925). And in a different way, much could be said about Ernst Lubitsch and Lady Windermere’s Fan, released in the same month. On this particular occasion, Morris focused on Johann Sebastian Bach’s The Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ according to the Evangelist Matthew. EM sees himself as being in this tradition: certainly it is crucial for understanding many of his individual films as well as his body of work as a whole. One should emphasize perhaps that the other side of this “Fuck You” approach is incredible rigor and discipline.

Well if Errol will let me, I will post that section of his talk sometime in the future.