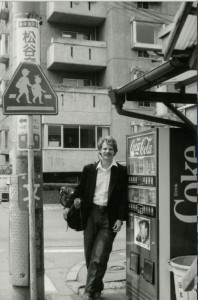

I went to Japan for the first time in March 1985 to show Before the Nickelodeon: The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter. My sponsor was Kenzo Horikoshi, who will always be a personal hero of mine. He had (and has) a small theater, called EuroSpace, and was also a distributor and art film producer. He screened my documentary at EuroSpace where it was immediately preceded by Basket Case, which Kenzo also loved. (From my perspective, the one thing these two films had in common–other than Kenzo’s enthusiasm––was that we had shared some of the same cheap film services in the Film Center Building, 9th Avenue and 45th Street in New York City.) Kenzo’s distribution strategy involved taking me all over Japan to show the film in small ciné clubs: while in Sapporo we did some spring skiing; while in Kyoto, we went to a night-time spring festival and drank beer under the cherry blossoms. Kenzo apologized for not getting tickets to the opening day of the Yomiuri Giants. We were going on the second day of the season––except opening day was rained out so the second day of the season became the opening day. It was that kind of trip. People loved the film (one local critic put it on his list for 10 best films of the year).

I went to Japan for the first time in March 1985 to show Before the Nickelodeon: The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter. My sponsor was Kenzo Horikoshi, who will always be a personal hero of mine. He had (and has) a small theater, called EuroSpace, and was also a distributor and art film producer. He screened my documentary at EuroSpace where it was immediately preceded by Basket Case, which Kenzo also loved. (From my perspective, the one thing these two films had in common–other than Kenzo’s enthusiasm––was that we had shared some of the same cheap film services in the Film Center Building, 9th Avenue and 45th Street in New York City.) Kenzo’s distribution strategy involved taking me all over Japan to show the film in small ciné clubs: while in Sapporo we did some spring skiing; while in Kyoto, we went to a night-time spring festival and drank beer under the cherry blossoms. Kenzo apologized for not getting tickets to the opening day of the Yomiuri Giants. We were going on the second day of the season––except opening day was rained out so the second day of the season became the opening day. It was that kind of trip. People loved the film (one local critic put it on his list for 10 best films of the year).

As part of promoting the documentary, Kenzo had me give a presentation to a large Tokyo audience while I was in the midst of serious jet lag. He also had a small entourage of young cinephiles around him, one of whom was a graduate student (like me) interested in early cinema: Hiroshi Komatsu. Hiroshi and I went on to collaborate on an essay entitled “Benshi Search” –about “the last benshi,” Matsuda Shunsui, and his student, Sawato Midori. Now Hiroshi is Komatsu Sensei, head of the cinema section at Waseda University and it is he who invited me to the conference. And so, some 27 years later I am back for my second Tokyo presentation (though I have been to Japan a few times in the interim, notably in Kobe for the 1995 conference that celebrated the 100th anniversary of cinema). In 1985, I had brought a bottle of Jack Daniels as a gift for my sponsor Kenzo Horikoshi. Now, it was with the greatest pleasure that I brought a bottle of Wild Turkey to give to my current sponsor, Hiroshi Komatsu.

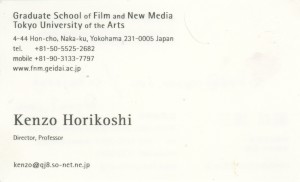

Kenzo has also moved into academia, setting up the Graduate School of Film and New Media in Tokyo University of the Arts–the first and only national program in filmmaking in Japan. He is the director-professor. Horikoshi Sensei will also be taking Kiarostami’s latest film (entitled The End), which he has just finished producing, to Cannes. (As for HK and KH, it is worth noting that Komatsu went to Tokyo University of the Arts, while Horikoshi went to Waseda–so it is more than their initials that the two have flipped.)

Although I am considered a regular at Kodama Restaurant on 45th Street and 8th Ave in New York City (I have my own bottle of Sochu behind the bar), Japanese food in Japan is something special. My handler, Masaki Daibo, took me to a local bar. A favored hangout for some––and not too expensive: the food and Sochu were great. And, since it was one of comparatively few bars open on Sunday, I ended up returning the next evening. FYI: Daibo took most of the photos for this blog entry. (Thanks Masaki)

If you, dear reader, expect me to blog a conference in Japan on 10-hour jet lag, you have unrealistic expectations. The conference was on Acting and there were several other keynote speakers I enjoyed hearing: Erin Brannigan, an Aussie who has published Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image; and Paris-based Christian Biet, who teaches brief stints at NYU, represented Theater Studies, but spoke in French. Kim Soyoung, a Professor of Cinema Studies at Korean National University of Arts, is ABD from NYU’s Department of Cinema Studies, makes films (mostly documentaries) and writes books (in Korean, though she has essays in English and presented her paper at the conference in English). She shared an essay on early cinema in Korea which situates it within a larger media framework that includes public oratory and initial efforts to build a democratic movement. We seem to be thinking along similar lines.

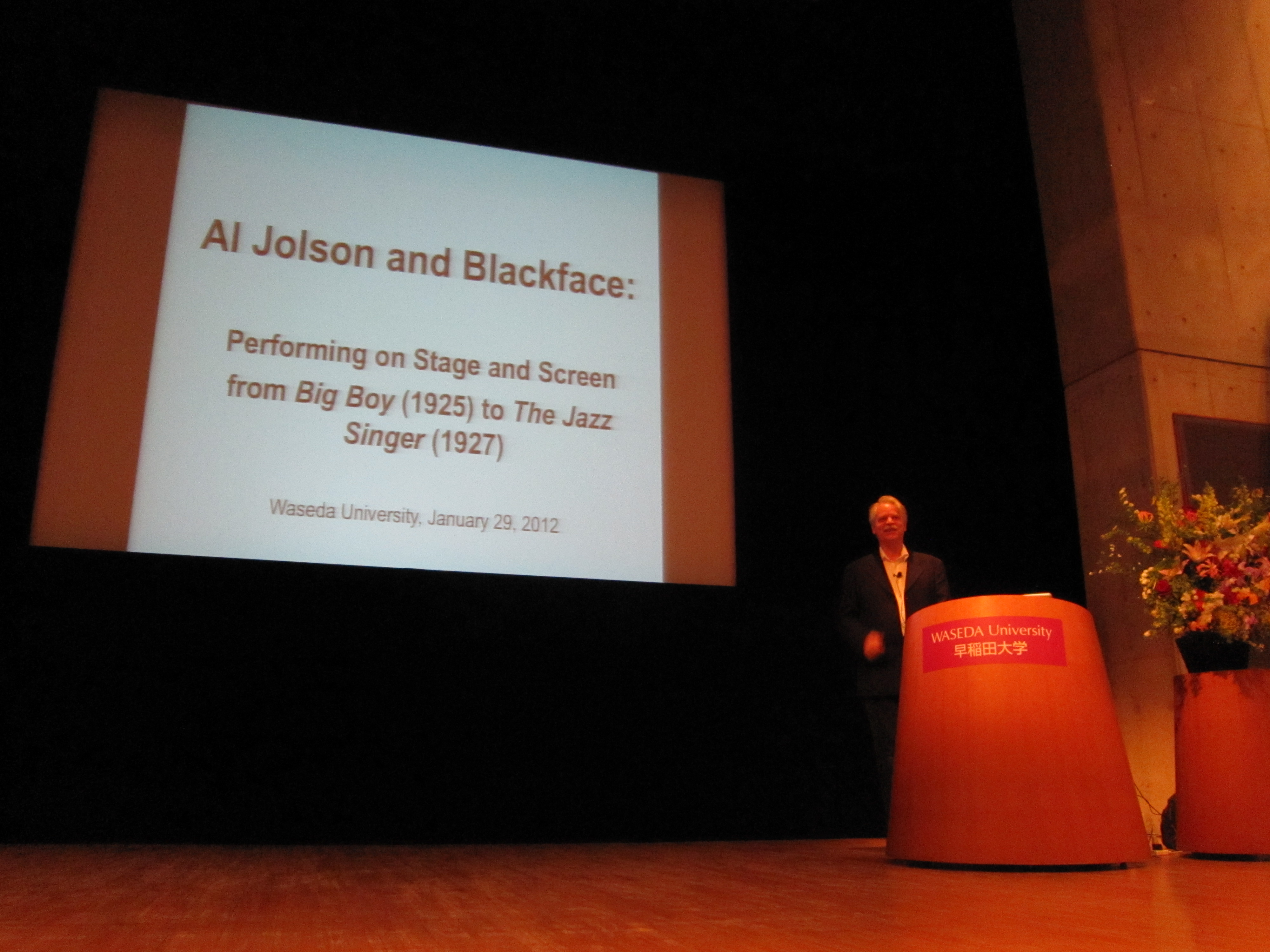

My own talk “Al Jolson as a Performer: Moving from Stage to Screen” was delivered with a slightly different title and built on recent work I have done on The Jazz Singer. In brief, motion picture acting has often been understood as a more restrained variant of stage acting (even to the point of being non-acting). However, Jolson shows how this rule of thumb can lead us astray–and facilitate the widespread conviction that his blackface performance demeaned Negroes and was racist. As a performer on stage, Jolson regularly moved in and out of character–from being Al Jolson in black face to being Gus, the Negro character that he played in his musical reviews. In Big Boy (1925) he used this performance style to align himself with his fellow black performers and to play with the color line in ways that were transgressive. When he moved to film, however, Jolson also shifted to a coherent, naturalistic acting style. This worked well enough for The Jazz Singer, where the oscillation was displaced onto a different level (black face as the mask of theater vs. the Rabinical robes of orthodox Jewish religion that his father wore). But when he starred in the 1930 film version of Big Boy, his uni-vocal approach undermined his stage achievement. I threw in a little Marx Brothers: Chico in Animal Crackers, whose Jewish identity is momentarily exposed as Roscoe W. Chandler (formerly known as Abie the Fish Peddler) wonders how he became Italian.

One of the real pleasures of the trip was meeting the group of graduate students clustered around Komatsu. Three of them are going to Boston to attend SCMS in March. Now they are going to make a second stop in New Haven to meet some of their Yale counterparts.

One of the real pleasures of the trip was meeting the group of graduate students clustered around Komatsu. Three of them are going to Boston to attend SCMS in March. Now they are going to make a second stop in New Haven to meet some of their Yale counterparts.

Pingback: » Waseda Film Studies Comes to Yale-with Jet Lag Charles Musser