The end of the school year meant there was no time to indulge in blogs and posts. So I am hoping to make up for lost time.

One event I want to document and remember is our celebration of Charlie Chaplin’s 123rd birthday.  The idea came about because we were looking for a way to show a film by Kathryn Millard, who is a Professor of Film and Creative Arts at Macquarie University in Australia and came to Yale as a visiting scholar to do research on Stanley Milgram and Milgram’s experiments on obedience, resistance and authority, which he conducted at Yale in the 1960s (I remember participating as a subject in some pale echo of these experiments when I was a Yale undergraduate but by then the experiments were being discussed ins Psych 101.) Kathryn contacted me about some kind of sponsorship because Milgram’s papers were at Yale and she suspected that we were soulmates in the academic sense. And indeed, this proved to be the case. Here is a small piece of her bio on the Macquarie University website:

The idea came about because we were looking for a way to show a film by Kathryn Millard, who is a Professor of Film and Creative Arts at Macquarie University in Australia and came to Yale as a visiting scholar to do research on Stanley Milgram and Milgram’s experiments on obedience, resistance and authority, which he conducted at Yale in the 1960s (I remember participating as a subject in some pale echo of these experiments when I was a Yale undergraduate but by then the experiments were being discussed ins Psych 101.) Kathryn contacted me about some kind of sponsorship because Milgram’s papers were at Yale and she suspected that we were soulmates in the academic sense. And indeed, this proved to be the case. Here is a small piece of her bio on the Macquarie University website:

Kathryn is a filmmaker, essayist and academic with a body of work that is internationally recognized and highly awarded. She holds a Doctorate of Creative Arts (1999) and an M.A. in Applied History (1993) from the University of Technology, Sydney. Both theses focused on the poetics of colour.

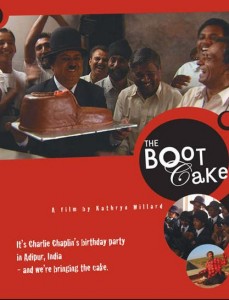

Our affinities go far beyond being filmmaker-scholars in an academic world that remains uncomfortable with that combination. I became interested in the Milgram experiments really due to Errol Morris who was concerned about the way they were being applied to the so-called “bad apples” at Abu Ghraib––the subjects of his documentary Standard Operating Procedure. The issue of obedience and authority, of course, gets played out in universities in very complicated and fraught ways–e.g. Yale University ca. 2012. Milgram’s experiments are related to Chaplin’s tramp in ways that should be obvious:, his screen construction –Charlie– is engaged in a massive project of resistance to the regimentation of work in industrializing America–he rejects obedience to authority in some deep way. Kathryn had made a documentary on Chaplin imitators, entitled The Boot Cake (2008) while it was my essay on Chaplin (“Work, Ideology and Chaplin’s Tramp”) that seems to have sufficiently impressed the search committee at Yale to get me hired in the first place.

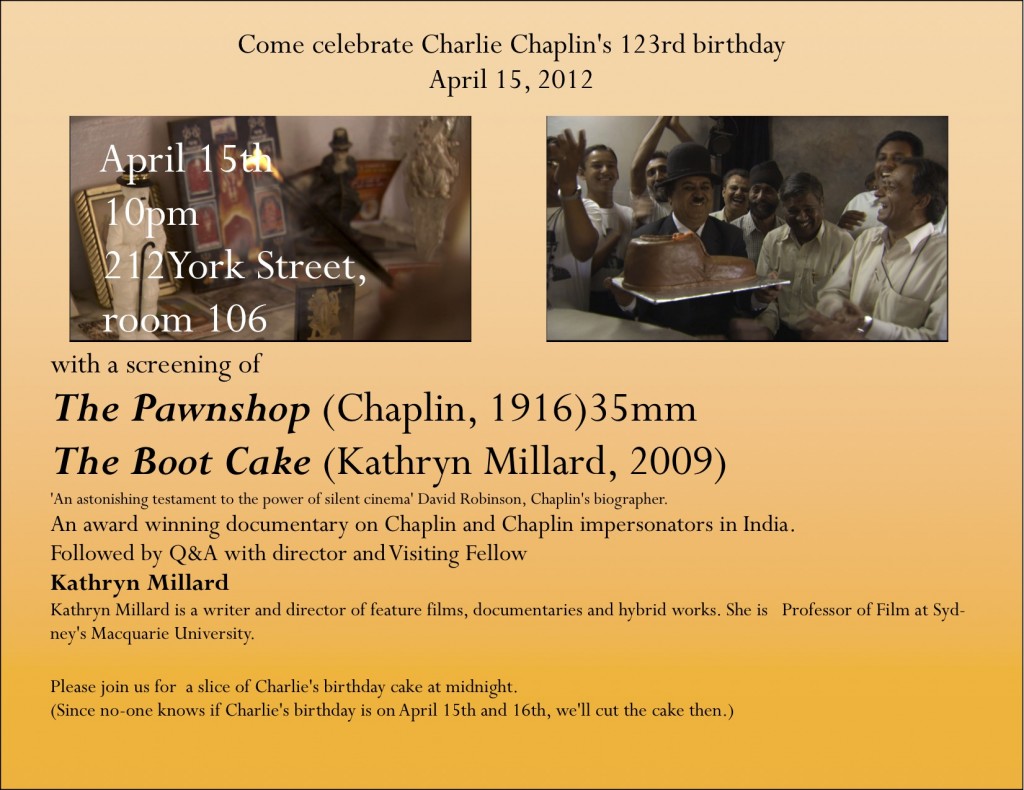

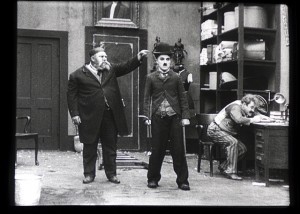

There is some uncertainty as to Charles Chaplin’s actual birthday. Was it April 15th or 16th? Generally people go for the 16th, but who knows? So we decided to have a party on the night of the 15th and then cut the cake at midnight. Before the cake cutting we showed Yale’s 35mm print of The Pawnshop (1916)–a key and glorious Chaplin masterpiece in my humble opinion–and Kathryn’s documentary.

Before the screening, as it so happened, we had scheduled one of our potluck dinners with Ashish Chadha, Ashwini Deo, Domingo Melina (who took Kathryn’s portrait at the top of this blog) and Maria Pinango–plus our kids.  Kathryn joined the group and then everyone found there way over to the screening. Since it was school vacation the next day, the kids had no curfew.

Kathryn joined the group and then everyone found there way over to the screening. Since it was school vacation the next day, the kids had no curfew.

Turn out was not the best, but the special treat for me was to watch Chaplin with the kids, particularly my son John Carlos. Although we avoid TV per se, our children see a lot of moving image programming from Netflix and elsewhere. John Carlos is a big Buster Keaton fan. But it is unusual for them to sit and watch a silent B& W film in a theatre-like setting–in the dark with complete focus and concentration. They laughed very hard. And very loud.  John Carlos loved Charlie Chaplin but found one moment very disturbing –when Charlie kicks a young boy in the buttock. Hitting the cop with a ladder was just fine, but that moment when he kicked the boy’s rear end proved to be of ongoing concern for the next few days. (“Why did he kick the boy in the butt, Daddy?”)

John Carlos loved Charlie Chaplin but found one moment very disturbing –when Charlie kicks a young boy in the buttock. Hitting the cop with a ladder was just fine, but that moment when he kicked the boy’s rear end proved to be of ongoing concern for the next few days. (“Why did he kick the boy in the butt, Daddy?”)

Next up was Kathryn’s documentary, The Boot Cake: The Boot Cake shows some clips of Chaplin imitators from the 1910s–actors who made their careers in the image of Chaplin, but most of the film was devoted to present-day Chaplinites. There was something quite moving about these people who remain devoted to the comedian almost 100 years after he began to make films. They are all, as Kathryn remarked, bad Chaplin imitators. Many are lost souls, who perhaps find in Chaplin a kindred spirit, someone who does not quite fit into the world around him.

The Boot Cake shows some clips of Chaplin imitators from the 1910s–actors who made their careers in the image of Chaplin, but most of the film was devoted to present-day Chaplinites. There was something quite moving about these people who remain devoted to the comedian almost 100 years after he began to make films. They are all, as Kathryn remarked, bad Chaplin imitators. Many are lost souls, who perhaps find in Chaplin a kindred spirit, someone who does not quite fit into the world around him.

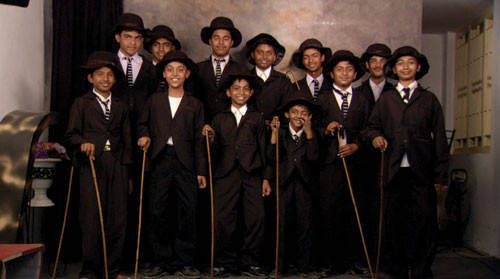

Kathryn’s film is centered around Chaplin imitators in India––and in particular a small cult in a town where Chaplin has become a kind of God,  and they make an

and they make an

elaborate ritual of celebrating his birthday with a boot cake, in memory of the boot that Charlie ate in The Gold Rush (1925). The local boys (and one girl) get dressed up in their tramp costumes.

The mastermind behind these events is a doctor who understands that laughter is good for one’s health. Among his prescriptions for patients are comedy DVDs. He first saw Chaplin in a movie theater as a kid–and stayed for repeated shows. Kathryn’s job–besides filming the doctor and the celebration–was to find a proper boot cake for the anniversary. In the process of following Kathryn’s journey of discovery via film, we learn that licorice is a laxative and that when Chaplin ate his shoe made of licorice for The Gold Rush (multiple takes and multiple shoes), he suffered the inevitable results for his art.

By the time we finished the screening of this documentary for adults, the kids were getting sleepy -and John Carlos was in dreamland. So after a few questions we moved to the cutting of our cake:

And then back to work! Kathryn had found a 91-year-old resident of New Haven who had participated in one of the Milgram experiments. He had been noncompliant–i.e. a resistor. So she hired Film Studies Ph.D. candidate Patrick Reagan, whose dissertation is on utopia and distopia in modern cinema, to film an interview with Milgram’s subject for her forthcoming documentary.

***