The Orphan Film Symposium unfurled at the Museum of the Moving Image, April 11-14, 2012. This was its eighth articulation. As always, the success of this wonderful gathering of scholars, archivists, lab technicians, digital geeks and independent collectors was due to mastermind Dan Streible.

The renovated Museum of the Moving Image was filled with Orphanistas though no one was turned away this year (I think!).

The presence of Tom Gunning at a conference guarantees its success, but in this instance Tom’s participation was simply confirmation that this event was the place to be. (Indeed, I abandoned the Environmental Film Festival at Yale and skipped the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival at Durham to be here.) He helped kick off the conference on Wednesday evening with a screening of Valy Arnheim’s The Elevated Train Catastrophe (1921, The 16th Sensational Adventure of Master Detective Harry Hill). In classic Musser fashion, I had to miss the entire evening. I was still preparing my own Orphans presentation on 1948 presidential campaign films and the research dragged on and on –into the afternoon and late evening.

David Schwartz, chief curator at the Museum of the Moving Image, played host.

I am not going to try to blog this conference in any detail. David and I gave presentations about the use of media in presidential elections. He showed us his incredible website, The Living Room Candidate, for which he has gathered a rich array of presidential campaign commercials from 1952 to 2008.

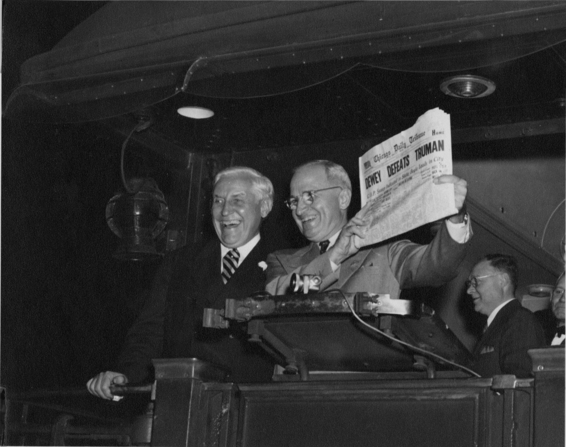

I provided his account with a little back story and showed three campaign films from 1948. Although motion pictures had been used to proselytize for various presidential candidates since the first months of cinema (i.e. Biograph’s McKinley at Home, Canton O., 1896), it was only in 1948 that the use–or misuse–of motion pictures for electoral campaigns had a direct impact on the outcome of an election. Governor Thomas E. Dewey had become the Republican nominee after winning a radio debate with his rival Harold Stassen–thus winning the Oregon Republican primary and securing the nomination. It was the first modern presidential debate in US history. A confident Dewey then hired Louis de Rochemont to produce The Dewey Story using reenactments and staged scenes with actors in the tradition of his series The March of Time. They planned to send 3,000 prints of the 10-minute film into US movie houses as paid political advertising. It was almost a formality since everyone was convinced that Dewey would easily defeat President Harry Truman on Election Day. Nevertheless, Truman protested and got his own campaign film–The Truman Story, which was made almost entirely of newsreel material and assembled at Universal. The Dewey Story was then released to the nation’s theaters as a public service on October 14th–and The Truman Story one week later. From a comparison of the two films, it seems almost certain that the people making the Truman picture had seen The Dewey Story and were able to make a much stronger film as a result. In any case, the powerful Truman film was shown to Americans after the Dewey picture and one week before the election. Recall that roughly 90 million movie tickets were sold each week in 1948, while just under 48 million people actually voted.

I provided his account with a little back story and showed three campaign films from 1948. Although motion pictures had been used to proselytize for various presidential candidates since the first months of cinema (i.e. Biograph’s McKinley at Home, Canton O., 1896), it was only in 1948 that the use–or misuse–of motion pictures for electoral campaigns had a direct impact on the outcome of an election. Governor Thomas E. Dewey had become the Republican nominee after winning a radio debate with his rival Harold Stassen–thus winning the Oregon Republican primary and securing the nomination. It was the first modern presidential debate in US history. A confident Dewey then hired Louis de Rochemont to produce The Dewey Story using reenactments and staged scenes with actors in the tradition of his series The March of Time. They planned to send 3,000 prints of the 10-minute film into US movie houses as paid political advertising. It was almost a formality since everyone was convinced that Dewey would easily defeat President Harry Truman on Election Day. Nevertheless, Truman protested and got his own campaign film–The Truman Story, which was made almost entirely of newsreel material and assembled at Universal. The Dewey Story was then released to the nation’s theaters as a public service on October 14th–and The Truman Story one week later. From a comparison of the two films, it seems almost certain that the people making the Truman picture had seen The Dewey Story and were able to make a much stronger film as a result. In any case, the powerful Truman film was shown to Americans after the Dewey picture and one week before the election. Recall that roughly 90 million movie tickets were sold each week in 1948, while just under 48 million people actually voted.

The Truman Story proved to be the key element in Truman’s come from behind, upset victory.

The Truman Story proved to be the key element in Truman’s come from behind, upset victory.

Otherwise, it was a chance to see a wide range of film material from the experimental work of Lillian Schwartz (Pixillation (1970), UFOs and Olympiad (1971), Enigma (1972), Papillons (1973), Galaxies (1974)) to booster films in the mid-1910s by Paragon Feature Film Company. Lillian was there–mostly blind and with limited mobility–but a sharp and witty mind.

Laura Kissel (U of South Carolina), Larry A. Jones (the Arc of Washington) and Faye Ginsburg (NYU Council for the Study of Disability) presented and discussed Children Limited (1951, Children’s Benevolent League), an advocacy film for children and families with intellectual disabilities.

The film depicted a supportive environment for these kids that was almost impossible to find in this period. It was a ground-breaking, progressive film that nonetheless could not escape the limitations of its period.

Between presentations and screenings, there was coffee (lots of coffee) and meals. It was a chance for all of us to catch up with friends we too rarely see:

I worked with Bob Summers back in the 1970s when he was running the Museum of Modern Art Film Circulating Collection. Paul Spehr, who needs no introduction after his magnificent biography of W.K.L. Dickson was someone I got to know very well at the Library of Congress in the 1970s and into the 1990s. Eli also worked in and around the Library of Congress–in particular on the pre-1910 AFI catalog.

If David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson have provided our Film Studies field with its longest running study date, Devin and Marsha Orgeron have reinvented the academic film couple in a way that has won my heartfelt admiration (in this I suspect I am not alone!) .

Full disclosure: At Oprhans 7, Marsha, Devin and I conspired to give Dan a lovely wall clock. See below:

It was Marsha’s wonderful idea–– a way to express our deepest, heartfelt gratitude to Dan. On 3/25/10 7:09 PM, Marsha Orgeron wrote:

Hi Charlie,

Just got a call today from the vintage store and the ugly frog wooden sculpture clock is all mine. I’ll pick it up tomorrow or Saturday.

On 3/26/10 3:56 PM, Marsha Orgeron wrote:

Hi Charlie, Snowden, and Skip,

This is the frog clock I picked up for Dan (see attached). It was actually handcrafted in Mt. Pleasant, S.C., which suggests to me a strong likelihood that the artist (such as he is) saw Ro-Revus as a child and that the frog never was far from his mind.… Hush….it’s a surprise.

In truth, Marsha and Devin developed some real affection for the little guy. Before finally parting with the souvenir, they added a small plague reading “For Dan Streible, rescuer of orphaned films, mascots, journals and scholars.”

But life at the Orphan Film Symposium is not all fun and games. Here Dartmouth professor Mark Williams is helping me teach Yale grad student Josh Glick (my advisee) a few lessons about conference schmoozing.

My basic lesson plan for the week was carefully crafted and rigorous: Day 1: Go to the Orphan Film Symposium; Day 2: Go to the Orphan Film Symposium, Day 3: ditto. After that, report back to me.

The last photo I took at Orphans 8 was of pianist Donald Sosin, whom I regularly see at the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy :

Then my camera battery died and the charger was in New Haven.

Charlie Musser has my heartfelt admiration for his presentation of A PEOPLE’S CONVENTION, yet another great discovery from the woefully understudied post-war U.S. documentary era. The Orgerons have my heartfelt admiration, too, but I want to hear more about how they’ve reinvented the academic couple. Like The White Stripes?

Jonathan–any comments about academic couples is probably fraught or else deserving of an extensively ethnographic survey. If I had only gotten a photo of you and Jennifer, I could have elaborated on this mode of being. In any case, congratulations that you are both going to be at UC-Santa Cruz! My own efforts in this direction can only be described as a pitiful, ongoing failure. But back to Devin and Marsha. I think Devin’s hat is part of the equation. To have a hat like that as part of his uniform (like my leather jacket)–and make it totally work. I am awestruck. But then I always wanted to be Buster Keaton when I grew up. Moreover, Devin’s hat is somehow complemented by Marsha’s glasses. Anyway, I’d like think the photo somehow captures an essential quality of their dynamic. Of course, Devin and Marsha are also editors of The Moving Image, which somehow escapes the rigidification of academic publishing. Anyway, they are amazingly cool because they are so down to earth yet possess a quirky sense of humor. Look at the frog clock that they got Dan (see above). Now that they must feel excessively analyzed, I’ll stop. But to the extent that they represent one strand of Film Studies’ future, I am feeling hopeful.