These remarks are based on my presentation of Industry’s Disinherited at the 9th Orphan Film Symposium in Amsterdam on April 2nd. We screened a digital transfer of the film courtesy of the UCLA Film and Television Archives. Images are from a digital file from a print at the Yale Film Study Center. More about these variant prints at the end of the essay.

Obsolete Format, Obsolete Film and Obsolete People:

The Case of Industry’s Disinherited (1949)

With the theme of obsolescence, the Ninth Orphan Film Symposium provided an irresistible opportunity to show another documentary produced by Union Films: Industry’s Disinherited (1949), which focuses on the fate of older workers who are “retired” without sufficient financial protection.

At this symposium we are particularly concerned with issues involving the obsolescence of audio-visual materials—both particular works but also film formats such as 16mm celluloid or 68mm nitrate as well as analog and digital video formats. While it is important to consider the potential opportunities and challenges associated with obsolete audio-visual materials that have been found un-useful to the capitalist system, it is important to remind ourselves that obsolescence has had and will continue to have real life consequences for people.

People become obsolete in at least two ways. Rapid, large-scale changes in media practices can discard people in long-established job categories. And, of course, people get old and wear out. In the United States, certainly, the Humanities have been labeled obsolete. STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering and Math––is corporate academia’s current darling. Although some of us are still fortunate enough to have secure positions we find out budgets scaled back in problematic ways. In the United States we have a huge population of adjuncts who are paid pitiful wages: a reserve army of labor that is always on the verge of becoming professionally obsolete. Of course the sciences now face funding cutbacks and many science graduates are also finding themselves part of a new reserve army of labor, like professional football players always on the verge of being replaced by cheaper more up-to-date labor—in short being made obsolete.

People become obsolete in at least two ways. Rapid, large-scale changes in media practices can discard people in long-established job categories. And, of course, people get old and wear out. In the United States, certainly, the Humanities have been labeled obsolete. STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering and Math––is corporate academia’s current darling. Although some of us are still fortunate enough to have secure positions we find out budgets scaled back in problematic ways. In the United States we have a huge population of adjuncts who are paid pitiful wages: a reserve army of labor that is always on the verge of becoming professionally obsolete. Of course the sciences now face funding cutbacks and many science graduates are also finding themselves part of a new reserve army of labor, like professional football players always on the verge of being replaced by cheaper more up-to-date labor—in short being made obsolete.

Staying closer to the immediate concerns of this conference, I will focus on the audio-visual field, where we have been experiencing the final dissolution of a massive photochemical formation that had flourished for just over a century.  In New York City, DuArt closed its film laboratory last year and is in the last stages of emptying its film vaults. Unlike some labs that just closed, DuArt has tried to make the transition to video and digital media. A few of its employees retooled. But it would be interesting to have some metadata on what happened to those people it had employed even 10 years ago. As film studies has morphed into media studies, we have been more able to think about film as part of a larger field that includes radio and television.

In New York City, DuArt closed its film laboratory last year and is in the last stages of emptying its film vaults. Unlike some labs that just closed, DuArt has tried to make the transition to video and digital media. A few of its employees retooled. But it would be interesting to have some metadata on what happened to those people it had employed even 10 years ago. As film studies has morphed into media studies, we have been more able to think about film as part of a larger field that includes radio and television.

In this regard I think of Industry’s Disinherited as the twin of Old Radio Bonfire (NYC, 1929), a uncut scene in the Fox Movietone Collection at the Moving Image Research Collections @ USC, screened at Orphans 9 on Monday, March 31st. Certainly, as these two films prove, in the world of capitalist creative destruction, it is much easier to dispose of radios than of the people who built them––provided they have a union.

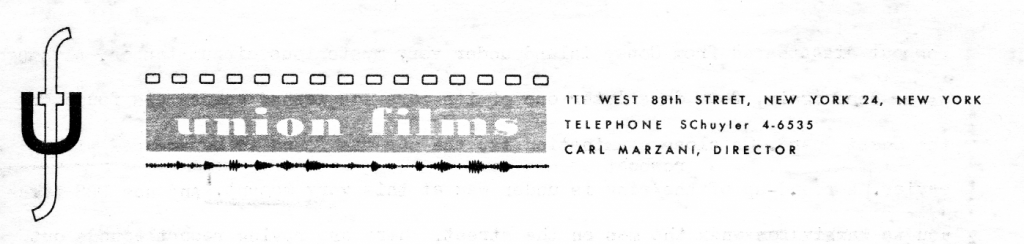

Industry’s Disinherited (1949) was made by Union Films, which was active in production between 1946 and 1953 and continued in distribution into the 1960s.

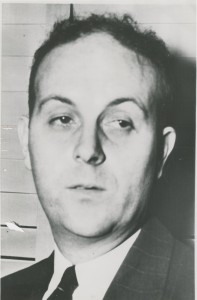

Its founder was Carl Marzani, who had become involved in filmmaking during World War II while working for the OSS, producing War Department Report (1943), which was nominated for an Academy Award. After the War, Marzani began a long association  with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers (generally called “the UE”), one of the most radical unions in the war and post-war period. By the end of World War II, UE had over 600,000 members, many of whom built radio and television sets which turned broadcasting into a mass media. Union Films’ first production, Deadline for Action (1946), which can be seen on the Internet Archive, severely criticized the corporate system, particularly General Electric and Westinghouse, which the UE had unionized, even as it advocated for change through the ballot box. In January 1947, with the encouragement of General Electric, the US government indicted Marzani for perjury, asserting that he concealed his past as a former member of the Communist Party when he joined the government. Convicted in May and mostly out of jail while he appealed the verdict, Marzani continued to make films both for the UE and other political organizations, notably the Progressive Party and Henry Wallace’s campaign for president in 1948.

with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers (generally called “the UE”), one of the most radical unions in the war and post-war period. By the end of World War II, UE had over 600,000 members, many of whom built radio and television sets which turned broadcasting into a mass media. Union Films’ first production, Deadline for Action (1946), which can be seen on the Internet Archive, severely criticized the corporate system, particularly General Electric and Westinghouse, which the UE had unionized, even as it advocated for change through the ballot box. In January 1947, with the encouragement of General Electric, the US government indicted Marzani for perjury, asserting that he concealed his past as a former member of the Communist Party when he joined the government. Convicted in May and mostly out of jail while he appealed the verdict, Marzani continued to make films both for the UE and other political organizations, notably the Progressive Party and Henry Wallace’s campaign for president in 1948.

It is worth noting that we have screened a Union Films production at each of the last three Orphan Film Symposia: People’s Congressman (1948), The Investigators (1948) and A People’s Convention (1948). Industry’s Disinherited moves into the year 1949.

In March 1949, Marzani lost his appeal and was sent to federal prison, where he would remain until July 1951. Union Films functioned in many respects as a collective and so it continued to make films under the leadership of director Max Glandbard, cinematographer Victor Komow and Marzani’s wife and business manager Edith Eisner Marzani. Union Films remained productive in 1949, making four ten-minute films that looked at the economic and political situation in post-War Europe and Israel.

In March 1949, Marzani lost his appeal and was sent to federal prison, where he would remain until July 1951. Union Films functioned in many respects as a collective and so it continued to make films under the leadership of director Max Glandbard, cinematographer Victor Komow and Marzani’s wife and business manager Edith Eisner Marzani. Union Films remained productive in 1949, making four ten-minute films that looked at the economic and political situation in post-War Europe and Israel.  They along with Industry’s Disinherited were funded through the United Electrical, Machine and Radio Workers. Industry’s Disinherited premiered at the UE’s annual convention in September 1949. According to the UE News,

They along with Industry’s Disinherited were funded through the United Electrical, Machine and Radio Workers. Industry’s Disinherited premiered at the UE’s annual convention in September 1949. According to the UE News,

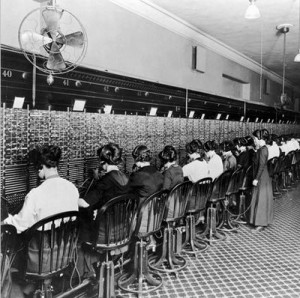

Union Films sent its cameraman to Bridgeport and Schenectady to “shoot” pictures of retired UE workers. The artful camera work takes the audience right into the problems of the old folks whose faces offer dramatic testimony about the hard times that they are suffering.

By smooth-running commentary and use of occasional animated cartoons and charts, “Industry’s Disinherited” develops the story of the five million people over 65 years of age who have to depend on some form of charity to make ends meet. (“Old Age–A Time of Rest,’”UE News, Sept. 10, 1949, 10)

General Electric’s headquarters were in Bridgeport, where it manufactured many of its radios and televisions.

Historian turned film distributor Amy Heller has written about the political dynamics within the UE’s Bridgeport local 203 both internally and in relation to the International headquarters in New York. The right and left wings of Local 203 battled for dominance between 1944 and 1950 as it elected anti-communist slates in 1944-45, 1947 and 1950. The left, which shared its political sensibilities with the New York office, regained control in 1947 and maintained it through December 1949. The UE, which had supported Henry Wallace in the 1948 presidential elections and rejected the anti-communist witch-hunts that were becoming increasingly common in the labor movement, was increasingly on the defensive. It left the increasingly anti-communist CIO (Congress Industrial Organizations) in October 1949, which then started a rival organization that took over UE Local 203 in December 1949. Industry’s Disinherited was the last motion picture that Union Films made for the UE, until 1953 when Marzani, who had a job with the UE after he got out of prison, produced The Sentner Story.

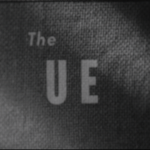

This political struggle provides the context for the making of Industry’s Disinherited. It was addressed UE workers in particular but a much larger public in general. It was dealing with essential bread and butter issues––that even the vast majority of workers who worked for large, prosperous US corporations did not receive pensions and had to rely on grossly inadequate social security payouts––in contrast to corporate executives whom received generous retirement benefits. It is worth noting that the copy we screened from the UCLA Film and Television Archive is missing an initial head title, which indicates that this documentary was a presentation of the UE.  This issue had wide appeal and it may well have been that more conservative unions and other organizations were eager to show the film without the UE’s imprimatur.

This issue had wide appeal and it may well have been that more conservative unions and other organizations were eager to show the film without the UE’s imprimatur.

The UCLA print of Industry’s Disinherited is a good copy but has significant scratches and is missing the opening headtitle (“The UE”). The first section of the print from the Glandbard Collection at the Yale Film Study Center is badly warped. A restoration using several different prints may promise the best results.